The first volume of Phoenix offered a bleak portrayal of human nature, emphasizing how we are fundamentally little different from the ants and the beasts, and how our superstitious clamoring for eternal life is ultimately a self-destructive fool’s errand. Though individuals were occasionally able to rise above the small-minded perspectives and fanatical loyalties that defined them, the overall portrait of humanity was a grim one, a detailing of a species too preoccupied with personal glory to even achieve the philosophical unity with nature of animals. The only balm against this scorching condemnation was the assurance that at the very least, the events taking place were far, far before our time, a reflection of a less civilized era of humanity.

Phoenix’s second volume immediately discards that consolation, proudly announcing itself as a volume of the future. Human nature is perhaps malleable, but it is also consistent across the eras. Our quest for eternity is not halted by developments social, political, or technological; though we claim enlightenment time and again, each new conception of society is nonetheless bound by the same hopes and fears, the same desperation for recognition and terror at oblivion. No matter the era, we scrabble fruitlessly in the dirt, gazing with wonder up at the glorious phoenix.

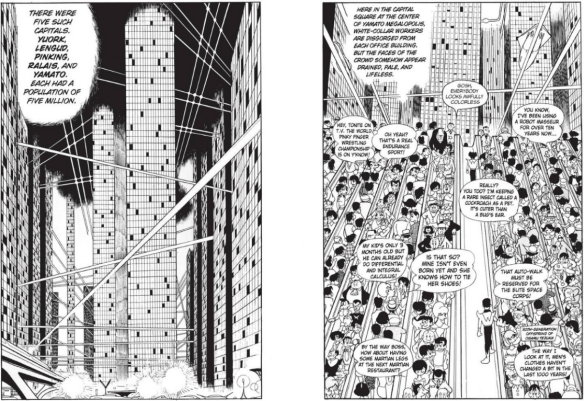

We touch down in the year 3404 AD, with Tezuka explaining that the world is on the brink of total environmental collapse. Life has withered away, and what dregs of humanity survive do so by huddling within five subterranean megacities, shelters illustrated through overwhelming panels of mighty towers and bustling crowds. Masato Yamanobe lives in Yamato, one such megacity, where he works as a space patrolman under his superior Roc. But Masato has a secret – he is actually harboring a “moopy” named Tamami within his apartment, flagrantly violating the very order he is paid to protect.

As Roc explains, moopies are alien life forms, visitors brought back from a distant planet. With no inherent shape of their own, moopies are able to take on basically any form, including that of a human. They are naturals at adapting to their environment – perhaps the exact opposite of human beings, whose natural tendency is to reshape their environment in a form more pleasing or convenient to their own needs. It is this tendency that has actually destroyed the world, as we contorted it into a form that is no longer self-sustaining or supportive of any kind of life. In our quest to reshape the world into a more desirable form, to make our mark on eternity, we have stolen the future of the planet.

The introduction of moopies as a new kind of sentient being immediately challenges our assumption of human beings as the protagonists of reality. Moopies are content with the world as it is; in fact, they can even share this contentment, inducing hallucinations in others and thereby transporting them into fantasies of the past. Roc sees this as an inexcusable retreat from the challenges of the present – mankind is wallowing in sentimental nostalgia, rather than facing the urgent crisis of the modern world. It was this threat that prompted the order for all moopies to be executed; but of course, Tezuka’s own perspective always stretches beyond our individual quests for eternity, offering a quiet question of whether moopies are simply here to comfort us in our old age, as our species rightfully fades into the past.

Masato Yamanobe expresses the contradiction of Roc’s command on a more individual level, as he laments his fate to Tamami. It was when he thought like Roc, destroying moopies without a second thought, that he was truly a monster. It was only through his love for Tamami, allegedly a threat to humanity, that he actually became human. Becoming heartless in order to ensure the continuation of humanity is in truth a rejection of all that makes humanity worthwhile. If we must sacrifice our kindness, our curiosity and empathy towards those unlike ourselves, in order to survive, then humanity is truly not worth saving. If it is a choice between that or oblivion, then let humanity at large pass into history, and a new chapter begin.

That question of whether humanity is even worth saving is central to this volume, and the answers provided are rarely flattering ones. Our would-be savior arrives in the form of Dr. Saruta, a genius obsessed with recreating the creatures of the old, once-fertile earth. Though he creates countless experimental subjects, they are all bound within his amniotic tubes, incapable of surviving in the open air. Saruta’s children point to the necessity of life surviving beyond human hands, to creatures like moopies carrying the spark of enlightenment forward when human ingenuity fails. Like mankind within their subterranean cities, the animals of Dr. Saruta can only live a pale imitation of life, an imprisonment of parasites who are incapable of self-propagation. “Can this be called life?” he wails.

Meanwhile, those cowering in the cities have become so disillusioned of their own potential as to cede their governance to a collection of supercomputers. We swiftly learn that Roc swears allegiance to “Hallelujah,” the computer governing all of Yamato’s actions. That name points to the tragic constancy of humanity; even this far in the future, we frame salvation in religious terms, seeing our hope of eternity as a dream provided by an accommodating shaman or deity. Though Roc scorns Masato for not prioritizing humanity over his lover, humanity itself has abandoned self-determination, seeing only the cold calculations of a computer as capable of making the choices necessary to ensure humanity’s survival.

Through these computers, Tezuka asserts that mankind’s nature is stable throughout history, that we will forever have a tendency to surrender our agency to the whims of an alleged higher being, and that communal understanding will always be thwarted by our preference for inarguable leaders over genuine, earnest individual connections. In their bickering over the relative superiority of this or that supercomputer, Roc and his parallel in the city guided by “Danuba” seem little different from the superstitious humans of the first volume, each certain that their deity is humanity’s true guide. And in ceding our agency to these computer-gods, it seems similarly clear that humanity is already dead – that we have abandoned the light of inspiration in favor of the cradle of security, essentially making us no difference from the helpless, static animals of Dr. Saruta’s laboratory.

The concerns dominating Tezuka’s own world are clear in the attitudes and fears of his far-flung characters. Roc sees the fashion and individual choices of the surviving humans as signs of “decadence” that must be eradicated. In his determination to follow only Hallelujah’s directives, he has ensured humanity exists within a cage that does not allow for any of the individual choices or beliefs that actually make humanity worth protecting. Like many military leaders at the top of fading empires, he sees austerity, groupthink, and fascism as the only ways to restore humanity’s strength. The specifics might be different, but the world within these megacities is ultimately akin to that of Germany in the leadup to World War II.

Similarly, the ultimate result of this system feels both familiar and inevitable. When Hallelujah and Danuba are brought into direct conversation, they swiftly decide that the only “logical” answer to their disagreement is war. These computer overseers have only replicated the violence they were intended to replace, driving humanity into the same self-destructive patterns that have recurred across human history. A computer designed by man will ultimately just reproduce the results of man, echoing the same furious refusal to see another’s perspective that informed the brutal wars of Phoenix’s first volume.

But Tezuka, as always, takes the long view. As humanity’s last remaining sanctuaries are incinerated by nuclear explosions, the second half of this volume blooms into a marvelous exploration of the long, gradual process of life’s formation. The rich visual vocabulary Tezuka forged over a lifetime of writing fantastical comics, comics that would go on to provide a template for manga storytelling, is here directed towards making the building blocks of existence feel as wondrous as any great voyage or climactic battle. After a lifetime of imagining thrilling marvels to delight his audiences, Tezuka has come to realize that there is nothing more thrilling than the marvel of life itself, and has committed his pen to making that glory understandable to all.

With Masato chosen as the observer for the earth’s slow rebirth, Tezuka offers gorgeous panels of Masato and the phoenix beside him exploring the building blocks of life, drawing a visual parallel between individual atoms and the glory of the cosmos. The phoenix burdens Masato with a might task: stating that the evolution that gave birth to mankind was a mistaken course, it now falls to Masato to find a better way. This assignment is accompanied by another astonishing series of panels, as Masato feels the weight of eternity collapse within him, overwhelmed by infinity as he is turned immortal. Through these panels, Tezuka frequently strives to visually convey something that is beyond the reach of words, to realize the grandeur and terror of existence in narrow comic panels.

It would be easy to spend an entire article marveling at Tezuka’s feats of paneling throughout this volume – the manic energy provoked by Roc fleeing through a literal spiral of panels, the simultaneously restrained yet impactful punchline of switching to a full white background for Masato’s attempted suicide, or even just the way diagonal lines are used to create a sense of panels almost tumbling over each other, as if the story itself is impatient to be told. Phoenix’s second volume exhibits a formidable language of action storytelling, a masterful fusion of medium-specific tools and dramatic intent. At this point, Tezuka’s paneling is striving for mythological grandeur, and more often than not actually achieving it. His control of pacing and capacity for invoking awe are unbelievable.

To dive deeper into just one example, take the two pages below, which themselves offer a tidy microcosm of several of Tezuka’s paneling guidelines. First we have a row of strict conversation between Masato and Dr. Saruta, a straightforward exchange that is conveyed through equally straightforward, identical square panels. Like the rigorous nine-panel structure of Watchmen pages, these panels are designed specifically not to be seen, to disappear and allow the conversation to flow unmediated by any flourishes of paneling. Then there’s the full-length vertical panel of the rocket itself, a staggering visual setpiece that serves as a hard reset in tension, causing the audience to take a breath just before the energy begins to rise again.

That rise is conveyed through the ratcheting intensity of the rocket’s pre-flight preparations, conveyed through a stack of panels with diagonally placed gutters, such as to create a sense of sliding momentum as each panel leads the eye down towards the next. And finally, a full page of panels radiating from the top left like rays of the sun, creating a sense of awe and visual constancy as the eye is drawn up, up, and away from left to right, as if we are watching alongside Masato as the doctor’s vessel retreats into the cosmos.

Tezuka’s visual brilliance offers some comfort in what is far from an easy, uplifting journey. It is not just the individual tragedies of volume two that tug at the heart, but also the underlying philosophy, the fundamental understanding that humanity is not particularly special. Masato’s stewardship of the new earth does not immediately result in a new humanity; first, the earth is inhabited and then dominated by a species of hyper-intelligent slugs. Their clear similarities to human beings, both in the audacity of their dreams and the cruelty of their bigotries, emphasize that humanity was never inevitable. We claim our gods give us providence, but as both volumes one and two emphasize, our gods are always of our own making.

Tezuka’s breadth of perspective emphasizes how humans are just another form of animal, as concerned with survival and self-propagation as any other. Humans are not unique or blessed by the gods – they are simply history’s lucky victors, their dominance a random quirk of fate. But this thought should not lead us to despair regarding our lack of significance – it should lead us to gratitude and taking greater care in managing our environment, knowing as we do that there is nothing “destined” about our dominance or survival. We were lucky so far, but if we want to preserve what is great about humanity, we must work with all our might to protect the world we inhabit. “Our progress was fatal,” laments the last slug at it collapses in the wake of a self-inflicted apocalypse. The beasts of the land understand that they will live for a time and then pass from the earth – can us “enlightened” beings ever learn to accept the same?

That is the hope, at least. Masato’s journey takes him from passionate, forbidden love all the way to the end of the cosmos, as he comes to accept his place within the great flow of nature, the collective organism known only to the phoenix. Masato and Tamami are ultimately reunited within that flow, wisps dancing in perpetual harmony, a great flow of consciousness that is the life of the universe. Humanity marches onward, desperate for eternity, losing sight of the ground beneath in its grasping for the light above. Can we overcome our hubris, our tribalism, our self-destructive greed? Perhaps not; perhaps all we can hope for is that we do not break the precious gift that is life on earth alongside us.

This article was made possible by reader support. Thank you all for all that you do.