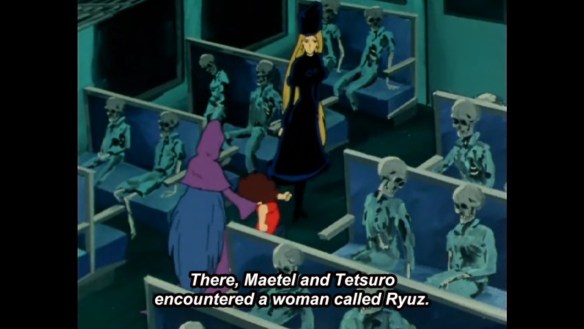

Hello folks, and welcome back to Wrong Every Time. Today I am eager to hop back aboard the Galaxy Express 999, whose recent cliffhanger has left Tetsuro kidnapped by the mysterious Ryuz. Curiouser still, it appears that Maetel possesses some knowledge of this woman; Ryuz explicitly stated that Maetel was “beyond her grasp,” and though Maetel attempted to dissuade her, she ultimately put up little resistance to Ryuz’s kidnapping of our poor boy.

What all of this means is still a mystery, largely owing to our fragmentary understanding of Maetel herself. It’s clear she is connected with the Galaxy Express’ parent organization, most likely an heir of its manager or creator, and that she is herding Tetsuro towards some ominous secondary objective. The fact that Ryuz couldn’t claim her could point to her political importance, her secretly metal body, or something else entirely; regardless, I am perhaps most intrigued to further explore Ryuz’s time-distorting powers, which offer an interesting counterpoint to the story’s prior thoughts on time. We have mostly focused on the loneliness of eternal life within a metal shell, but the brevity of a human life offers its own sort of terror, particularly given the absurd scale of space travel. So is it more tragic to embrace such a brief flicker of existence, or to be the one left to mourn the passage of those who do? Let’s find out!

Episode 8

“The Graveyard At The Bottom Of Gravity” remains a perfectly Matsumoto title. Scientifically inscrutable, but profoundly evocative – that’s the scifi fantasy way

I remain charmed by Tetsuro’s relative helplessness within this narrative – Ryuz grabs him without difficulty, and then we get some lovely animation of his wobbly little limbs windmilling uselessly against her strength. I appreciate that this show lets its protagonist be a fragile boy within a vast, terrifying world – it makes space feel all the more overwhelming, and seems more honest than a take-action shonen lead would feel

“However, Maetel did not even attempt to stop her.” Even the recap draws attention to Maetel’s seeming powerlessness in the face of this woman

Of course, it’s not like the Galaxy Express itself is any sort of benevolent institution. The train demands sacrifice and promises a false idol; it is only Tetsuro’s association with Maetel that allows him to enjoy its wonders at no cost

“Moving time and moving yourself are two entirely different things.” Ryuz’s space ship is apparently a bit of an antique. One detail at a time, we seem to defining her as in total opposition to the gilded cage of the Galaxy Express

Ooh, love this mournful vocal melody as we return to Maetel. The distinct convergence of synths and popular vocal styles of the ‘60s and ‘70s offers us a specific sonic aesthetic of mid-century science fiction, with melancholy, warbling vocals and lots of ostentatious synth noises. The original Star Trek offers a similar conception of “space music,” which over time has come to evoke space fiction even in the abstract; you hear synths and theremins, you think aliens

Maetel informs the conductor that Tetsuro “went on a trip for a little while.” She sits comfortably on the 333, undeterred by the threat of aging, seemingly confident that Tetsuro will return. Is this how she expresses her faith in him?

Tetsuro arrives at Ryuz’s planet, landing in a bog next to an ominous raised cabin, like a tiny chapel lost deep in a bayou. If what you are offering your audience is compelling, you often don’t need to concern yourself with “justifying” it in a worldbuilding sense. Audiences suspend their disbelief so long as they’re enthralled; keep showing them new wonders, and they likely won’t stop to ask who built all this stuff

Of course, that’s distinct from “write whatever you want.” Stories demand internal consistency, and Galaxy Express has maintained a pretty consistent fantastical tone

Evocative yet minimalist compositions as Tetsuro approaches, offering little more than barren tree trunks rising out of heavy mists. You don’t need intricate details if you’ve got alluring core concepts – and of course, for a horror episode, obscured implication actually makes the scene more frightening

The stairs to her home are littered with skeletons. “These are all people who didn’t listen to what I said. So I moved time forward.”

“You’re sick because of the skeletons? You have one, too.” I’m reminded of their visit with the Space Pirate Antares, and how he drew attention to the bullets in his body that would one day kill him. The emphasis on our mortal flesh and bones serves as a perpetual reminder of mortality; there is little that separates us from those who have passed, only the briefest spark of life

“But why did you turn them into skeletons?” “Because none of them liked me and I didn’t like them either.” Well, that settles that

“There’s no God in space. Only the truth of creation and the flow of time.” Ryuz has apparently seen some shit

The center of Ryuz’s house is a vast control room with monitors revealing “the whole flow of space”

It seems like Ryuz may know too much to be happy – she has witnessed the overall flow of space and time, she understands completely that every human journey ends the same way, and thus she cannot feel the same thrill of discovery and potential that draws Tetsuro forward. To know everything is a terrible fate; without curiosity to draw us onward, we are as ghosts watching the world pass by. Oddly, it is a sense of being incomplete that makes a human complete – a sense that there is more to discover, further mountains to climb

“No two places have the same flow of time.” I wonder if she’s referring to time dilation or some more mystical concept – or speaking purely in metaphorical terms, reflecting on how the “pace” of life in different locations is always different

Back on the 999, the conductor states he’s going to start separating the 333 from their train. Maetel replies that this won’t help given the gravity situation, to which he quotes the employee manual, stating “in any situation, the crew has to do its very best to ensure the safety of the passengers.” An interesting exchange, seemingly implying that trying to take action has value in its own right. The dividing line between them seems similar to that between Ryuz and Tetsuro – both Ryuz and Maetel know too much to believe the world can be changed. In contrast, it is ignorance that makes Tetsuro strong, and which compels the conductor to struggle on in an impossible situation

Ryuz reveals she controls the flow of gravity that’s keeping the 999 trapped

She also reveals she has a metal body of her own, though she hides its glimmering interfaces beneath her rough cloak

She offers to give Tetsuro one as well if he will stay with her

“I have dozens of mechanical bodies. They used to belong to train passengers.” Love that his motives are being directly challenged so early. So what is truly the purpose of your journey, Tetsuro?

“I’m not going to get a mechanical body at the cost of my freedom.” So that’s his complaint. And yet, everyone who has actually acquired a metal body seems to view it as a cage, an absolute restriction on their freedom

A flashback reminds us that it was Maetel who specifically promised Tetsuro that his eventual mechanical body would come with no strings attached. Yet it’s clear Maetel has other plans for him, meaning this might actually be Tetsuro’s best chance

Ryuz reveals she’s been alone for five hundred years. The length of time these mechanical people have been left to their devices points towards an ominous stagnancy in the galaxy at large. Has culture really not changed for five hundred years? Has the Galaxy Express been offering its false promise all that time, its overseers having essentially frozen time into a perpetual wage-slavery present? At a certain point, cultural and scientific stagnancy would actually be preferable to those who seek only to acquire wealth; actually, “cultural stagnancy” is what Disney is already pursuing, a perpetual assembly line of the same cultural products

A flashback reveals that Ryuz was actually a flamenco dancer back when she was still human. The color design is overwhelmingly red, the red of vital, living blood, the symbol of biological humanity

Some nice shots here conveying Ryuz as increasingly trapped as she dances towards a man bearing a monocle, caught in narrowing spotlights or the reflection of a glass

The man is named Baron Clock. He awaits a decision from Ryuz, but she cannot decide

“If you really love me, you’ll do what I want and change the way you look.” Ah, the truest sign of devotion, demanding someone change their whole identity

Thus she accepted a mechanical body to maintain the Baron’s love. The last shot of the flashback is her again trapped in glass, reflected in the Baron’s monocle

When other women claim similar mechanical bodies, the Baron is furious. He never wanted Ryuz, only the novelty of a unique lover

“Your fashion is now old and doesn’t do anything for me.” Even in his cruelty, he embodies mankind’s search for novelty, while Ryuz is now permanently trapped in that one moment of curiosity

“He threw me to the curb like some beat-up car!” Interesting, Ryuz framing those in mechanical bodies as aging tools

Ryuz reveals that her mechanical body was “accidentally” equipped with the power to manipulate time. I am persistently in awe of the fantastical conceits that Matsumoto will just happily declare without further explanation; the man is an inspiration

Tetsuro says he can’t stay here because “there are still so many things I want to do. I want to decide my future for myself!” He still possesses agency and an unknown future, even though he is ultimately seeking the same cage as Ryuz

“If I had possessed a heart like yours back then… Even though the person I loved asked me to do it…” She admires his spirit, and he in turn feels nothing but sympathy for her plight. Just another lonely victim of our fleeting passions and eternal consequences

“Maetel or freedom… one day, you will have to choose painfully.” Ryuz offers one final warning as she departs

Maetel reveals she knew Ryuz’s true nature all along, and that she would not harm Tetsuro. He pledges to one day see her again, once he has a mechanical body of his own. Our idle pledges to meet again, the threads connecting us across a lonely galaxy

And Done

Thus another lonely soul imparts their tale of love and loss upon Tetsuro, warning again that a mechanical body will not answer his heart’s cry. And yet, as these vignettes stack atop each other, it feels increasingly clear that Tetsuro’s yearning for a mechanical body is paradoxically the essence of humanity itself; for nothing is more human than to strive in vain, to reach towards the heavens in wonder, to seek greater understanding of the galaxy and of the self. To complete this journey of discovery is to stagnate, and eventually be left behind; it is the unsatisfied seekers who are always moving forward, inspiring others through their quest for reinvention and enlightenment. Is fulfillment even possible, or is the realization of a dream merely the prelude to a life of dreamless isolation? Tetsuro journeys on, his very ignorance of these questions reflecting the brightness of his spirit.

This article was made possible by reader support. Thank you all for all that you do.