Hello folks, and welcome back to Wrong Every Time. With several of my house’s long-term streaming projects concluded, this week has seen us buried in kaiju features, as we storm through Godzilla’s sprawling cinematic canon. It’s been delightful seeing both the concept of a Godzilla film and the context of such films within Japan’s rapidly evolving society shift over the years, as the big guy transitions from an object of terror or warning of violent consequence to a beloved defender of earth and friend to the children. We’re basically watching a cinematic monster of the week series constructed across half a century, finding new things to appreciate in both the broad shifts and incremental adjustments of this titanic franchise. Let’s start with the big guy’s second appearance then, as we burn down this Week in Review!

Having thoroughly enjoyed my journey through the filmography of stop-motion master Ray Harryhausen, I then decided it was time to embark on another fantastical film legacy, and thus finally screened the followup to the original Godzilla, Godzilla Raids Again. Filmed and set immediately after the first film, Raids Again sees Godzilla returning from his watery home, and once again terrorizing the Japanese mainland. With no superweapon to save them this time, Japan’s forces will have to bring all their might to bear on this second tussle with the terrible lizard.

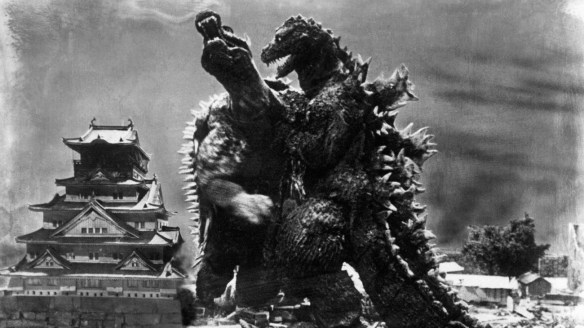

Though Godzilla director Ishiro Honda was too busy to direct this immediate sequel, his replacement Motoyoshi Oda largely maintains the awed, fearful imagery of the original, frequently framing Godzilla from a great distance or obscured by scenery. The big loss here is the sense of consequence; what struck me most about the original Godzilla was its frequent prioritization of the human aftermath, with many scenes focused on vast triage centers and injured victims. Honda’s wartime experience led him to make a solemn, mournful post-war dirge; in contrast, Godzilla Raids Again is more of an outright war drama with a sprinkling of horror, featuring more direct confrontation between military defenders and lizardly aggressors.

This shift drains Raids Again of some of the original’s poignancy, but the film is still richly adorned with its own pleasures. Oda’s black-and-white imagery is frequently astonishing; one particular sequence, where the army attempts to repel Godzilla by firing light bombs over a bay, feels like a dream half-remembered, with the threat of destruction fading to an inkling in the mind as the great creature roars beneath a light-speckled sky. Watching this film, I could immediately understand why Hideaki Anno was such a natural fit for a Godzilla film – as it turns out, Evangelion is already a Godzilla film, with its first episode largely contained within this film’s scenes of hopeless military holdouts. I am eager to see more!

We then continued our journey through the Godzilla franchise with its third film, King Kong vs. Godzilla. After laying dormant within his snowy grave for years, the king of kaijus is reawakened when a nuclear sub slams straight into his ice bed, prompting a new reign of mayhem. Meanwhile, the good employees of Pacific Pharmaceuticals are hard at work finding a new mascot, leading them to eventually float King Kong all the way back to Japan. This conflagration of idiocy resolves exactly as you’d expect, leading to an epic confrontation between the world’s biggest ape and lizard.

While the first two Godzilla films were created back-to-back, it would be seven years before Toho returned to the franchise, utilizing a story concocted by King Kong stop motion animator Willis O’Brien. It is likely this shift in source material, combined with the franchise dispensing with the obscured wonder of black-and-white photography, that results in such a different animal, in spite of the return of Godzilla’s original director Ishiro Honda. While the first two Godzillas drifted between war drama and horror, King Kong vs. Godzilla is a humor-filled adventure film, and the first entry in Godzilla’s apparent pro wrestling career.

Honda clearly understands he is constructing a different sort of film here; in fact, the employees of Pacific Pharmaceuticals feel almost metanarrative in their commentary, reflecting on how to “make kaijus sell” in a manner that feels ripped straight from the discussions regarding this film’s production. Nonetheless, while King Kong vs Godzilla basically abandons the beauty and terror of its predecessors, it replaces that with a generous apportioning of family-friendly mayhem, ending in a dramatic pair of battles between its two titans. If you want to see King Kong attempt to shove a tree down Godzilla’s throat, you should absolutely give this one a watch.

At this point, continuing with the adventures of Godzilla was going to require some supplementary readings, as the menacing creature began to draw kaijus from entirely different movies into his orbit. I thus screened Rodan and Mothra in quick succession, both directed by Godzilla’s own Ishiro Honda, and each of which demonstrated the variability of kaiju cinema in its own way.

Rodan was released back in 1956, and served as Toho’s first color kaiju feature. Black and white photography was essential to the terror of the first Godzilla films, and Honda’s response to the advent of color reflects an understanding that there’s no going back to the ominous ambiguity of the genre’s origins. Instead of slow-rolling the obvious and relying entirely on the majesty of the monster in question, Rodan is tightly packed with a murder mystery drama preceding its titular beast’s appearance, as miners and policemen seek out whatever man or monster has been killing workers in the depths of a local coal mine.

The trail of bodies eventually leads us to our supersonic adversary, a pterodactyl-like creature that can topple buildings with the force of its wings alone. Rodan is frankly a bit of an awkward kaiju all things considered, as it can’t really stop and face off with other giants without looking ridiculous; it is designed for high-speed flight, and in its debut at least, it gets to embody the distinct fear of a sudden bombing run, a malevolent force breaching the clouds with too much speed to ever escape. And the best image is saved for last: Rodan engulfed in magma, screaming for its dying mate as humanity ponders the beauty they have destroyed.

In contrast with the “paying for humanity’s past sins” inevitability of Godzilla, Mothra offers a very different kind of kaiju feature. Its overall structure is clearly more indebted to King Kong than Godzilla, centered on a succession of trips to the mysterious Infant Island. After several shipwrecked soldiers in an area known for “Rosilican” (very clearly Russian + American) nuclear tests turn up mysteriously free of radiation, a plan is devised to visit and learn the secrets of this island, funded by Rosilican entrepreneur Clark Nelson. They discover the island is protected by two pint-sized fairies, who everyone except Nelson agrees to keep a secret. Unfortunately, one capitalist apple ruins the bunch, and Nelson soon returns to capture the fairies, forcing them to sing for his quasi-carnival production until their songs summon the island’s true protector Mothra.

The messaging is pretty pointed in this one; Nelson is the smirking avatar of both capitalism and America’s paternalistic stewardship of Japan, and his schemes are precisely as petty and shortsighted as a one-man embodiment of the Bikini Atoll crimes ought to be. In contrast, Mothra’s fairies are nothing but pleasant even when they’re being captured and forced to dance for the crowd, politely warning anyone who’ll listen that Mothra will soon come and destroy them all.

Mothra is more adorable than threatening in both its larval and winged incarnations, the margins of the film are filled with endearing friends of the fairies, and Jerry Ito steals numerous scenes in his performance as the gleefully mercenary Nelson. Additionally, I’d say this is the first film to regain the sense of awe inherent in the first two Godzilla features, which the transition to color had previously lost. There is something genuinely transcendent about Mothra; the confidence with which its private world is constructed, the long slate of premonitions before it actually appears, and the restraint with which it is actually shot all collaborate to make for a kaiju that actually feels like a moral arbiter, the creature that will judge or redeem us. A shame humanity just can’t stop stealing her shit.