Seiya storms the barricades as we open Blue Flag’s fourth volume, first challenging his brother Touma on his reckless actions, then turning his barrels towards our other leads. As in his first appearance, Seiya cuts through all this adolescent anxiety like a hot knife through butter, casually dragging Taichi aside and challenging Futaba on her relationship with the pair of them in one easy gesture. When high school dramas only feature high schoolers, their perspective can get a bit myopic, naturally embracing the sense of consequence and finality that attends untested adolescent emotions. Emerging from childhood into anxious self-awareness, adolescents can naturally feel overwhelmed or paralyzed by the choices before them, seeing in each choice made an endless hall of potential doors that have all slammed painfully, permanently shut.

This is understandable; not only are they thinking about how their presentation and actions affect others’ impressions of them for basically the first time, they’re combining that understanding with the natural anxiety of high school, the first time in most of their lives where the stage after this one isn’t known or guaranteed. So they really do have the chance to screw up their lives in lasting, consequential ways, making it all the harder to make any key decisions.

The only antidote to this sense of paralysis is experience – making choices, seeing how they turn out, and realizing you still have the opportunity to make more choices afterwards. As frustrating as it is, the only answer to lacking confidence in your decisions is taking action, screwing up, and realizing life still goes on. And this “advice” is so trite it’s hardly advice at all, as both the peril and profit of embracing your chances will be different for every single person. But fortunately, people like Seiya are willing to push these anxious teens forward, to throw them in the pool and survey their attempts at swimming, making sure to extend an arm if it seems anyone’s likely to drown. Though all three of our leads fear breaking their fragile mutual bond, the only alternative to progress is stasis; what they have cannot last, but if they are brave, they could absolutely make something lasting out of it.

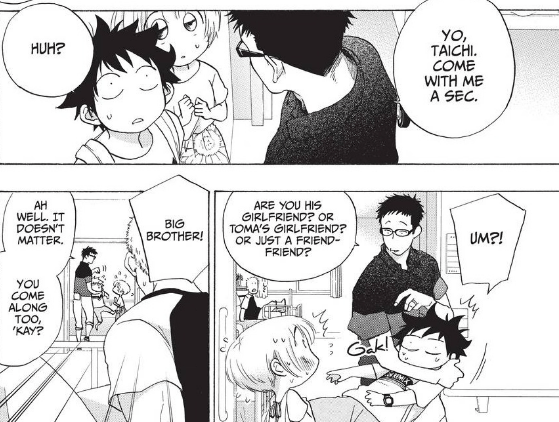

Incidentally, Seiya’s conversation with our leads also offers a fine demonstration of Kaito’s visual strengths; how they can balance realistic character acting with cartoonish superdeformed embellishments to evoke the specific tone of a moment, the balance of power between individuals, or how a conversation is perceived from one side versus the other. One of the very first things that stood out to me about Blue Flag was how much care Kaito took in how clothes hang on the human body, whether a given character is literally comfortable in their own uniform, or if they feel either constrained or shapeless within their clothes.

Here, Seiya demonstrates confidence and maturity in his loose-fitting polo T, while Taichi and Futaba have been reduced to wilting, superdeformed blob people. The dynamic is clear: our younger two feel like they’re getting a lecture from an adult, contracting into shapeless forms that seem like an inherent apology, like they’re preemptively cringing against whatever “trouble” they’re about to get in. Touma’s brother is inviting them to be frank with him, but they can’t match his confidence – instead, they default to the posture you’d see from note-passers being called to the principal’s office.

Later on, Kaito uses character blocking and panel positioning to accomplish a similar effect to the brother’s posture earlier. His turn to their genuine topic of discussion is illustrated through a panel where his black polo absolutely dominates the composition, his body curving up and around his two companions, their heads at such a distance that it appears they could just be sitting in his lap. This display of visual aggression, this play of visually dominating the scene, is further amplified by the following panel, a closeup shot of Seiya that simultaneously makes him feel huge and too close, a massive figure getting right up in your nose. Through these paneling choices, Kaito immediately shifts the tone of their encounter from a fond meeting with an older relative to an interrogation, our two leads utterly dwarfed by Seiya’s presence.

Taichi’s response is charming. He basically has to gather all his courage to ask Seiya the same question he asked, which only sort of annoys Seiya, but for Taichi embodies his fresh willingness to challenge Touma on his choices, to be the active friend and caretaker to Touma that Touma has been to him. This is an important emotional breakthrough for Taichi, but it’s of no use at all to Seiya – an offhand demonstration of one of this manga’s general talents, its understanding of the vast gulfs separating our experience and perception of the very same events. Seiya’s concerns are valid – Touma’s baseball career is over, his choice to get a job immediately after high school seems ill-considered, and the time to make such choices is swiftly passing. But he’s operating from a bird’s eye view, not taking Touma’s immediate feelings into account. In their inability to connect, the difficulty of true common understanding is made viscerally clear.

Seeing only two boys who are gambling with their futures for uncertain gain, Seiya leaves Taichi with one final, cutting piece of advice: “Sacrificing yourself is not how you show sincerity.” His words fly above the performative sacrifices of adolescence, emphasizing the give-and-take of genuine, meaningful relationships. You don’t prove the legitimacy or intensity of your feelings through hurting yourself, through sacrificing your own happiness for the sake of another. That’s frankly more for yourself than for anyone else, a way of convincing yourself or assuaging your guilt or otherwise paying penance for your actions. If you truly, sincerely want to help others, you must take care of yourself as well, and commit to becoming the greatest possible version of yourself, someone who can actually shoulder the load you intend to without collapsing beneath it. You must demonstrate a commitment to the future you intend to build – otherwise, self-destruction is just another method of running away.

With both the sincerity and efficacy of their mutual self-sacrificing in question, our cast pack in for one more awkward celebration: Touma’s hospital release party. The ride over to Touma’s offers a charming demonstration of the simultaneous complexity and simplicity of social drama, the theater of managing the various expectations, rivalries, and even hatreds across a larger group of teens. So much animosity and resentment, yet Futaba is able to calm everyone with the simple gesture of a piece of hard candy to enjoy on the road. At times it can seem like our feelings are impossibly far apart, but as this story consistently demonstrates, a little bravery and a little kindness can go further than anyone might expect. Futaba has been practicing being brave all throughout this manga, and at this point that practice has led her to be the one who’s often holding this group together.

Though Taichi arrives at this party with a mission from Seiya to discover Touma’s true intentions, he is sadly incapable of interpreting the relevant clues. Sneaking into Touma’s room, Taichi and his teammates discover a homemade board game locked in a puzzle box, a box that only Taichi knows how to open. A clear metaphor that speaks to both their long mutual understanding and Touma’s hidden feelings – only Taichi can unlock Touma’s heart, and the secret hidden inside is a talisman of their friendship, the special bond only they have shared.

The three tumble over each other in Touma’s rush to secure the boardgame, leaving all of them lying in a heap. Glancing up towards Futaba, Taichi is absolutely dazzled by her, Kaito’s art paying far greater attention to the pursing of her lips and shine of her eyes than usual, emphasizing where Taichi’s own attention is drawn. The portrait offers a snapshot of their current feelings – Futaba fully in love with Taichi, and Taichi recalling how fully he was entranced by Futaba from the start. But where does Touma fit into this picture? Bringing up the boardgame himself after the party, Touma’s intent to regain his original closeness with Taichi is clear. But as always, Taichi cannot assign himself enough value to complete the picture.

With the party concluded, the next chapter opens with a key memory of Taichi’s, one whose importance he’s only fully coming to understand in retrospect. Back when Touma was a latchkey kid being quasi-raised by his distracted brother, it was his stepsister Akiko who raised his spirits regarding his home life, leading them through a house-cleaning tour that returned comfort and control to his life. Now, in the wake of the party, Taichi sees that Touma has gone on another house cleaning storm, making the place spotless because it is all he can do. He cannot return certainty to his life, but he can maintain peace in his home – and to the ever-watchful Taichi, it is clear that this ritual reflects both his powerful feelings towards Akiko and his striving towards a sense of normalcy and routine that might now be forever out of reach.

We then reach a scene that could possibly use another Futaba hard candy intervention, as Taichi attempts to broach the topic of Touma’s post-school plans. The allegedly casual nature of their conversation seems to only make raising the subject more difficult; as Taichi stops and starts, his body language tucked-in and defensive even as Touma attempts to lighten the mood, you can practically see the membrane he is pushing against, the guard rails he’s established to avoid rocking the boat with his one irreplaceable friend. Kaito has a knack for both naturalistic dialogue and subtly expressive character acting, and both are put to dramatic work in articulating the invisible pressure points of these relationships.

The two maneuver around each other carefully, Touma probing for how much Taichi understands, Taichi hesitantly throwing out questions regarding Touma’s ambitions and romantic feelings. What most strikes me about this conversation is how logical yet limited each of their perspectives is; how their assumptions about each other are based on wildly incomplete information, and how that creates speedbumps in a conversation even when both of them are just trying to be frank with each other. Many writers have a tendency to equip all of their characters with some degree of “authorial voice,” a common understanding that facilitates graceful storytelling. Kaito goes in the opposite direction, stranding each of his characters on separate islands of information, equipping each of them with inadequate tools for coming to understand each other, and then building natural drama out of the friction that inherent situation creates.

Thus we get spreads like this dramatic challenge here, where Taichi asks if Touma has a crush on Aki-san. Taichi’s guess is right on the money in terms of what would work for who Touma used to be, and what would facilitate properly melodramatic action, but his failure in assigning his own flattering image of Touma and unflattering image of himself to his assumptions regarding Touma’s feelings means he is utterly blind to what Touma is actually struggling with. Their moods ebb and flow, with Touma shifting from amusement at Taichi’s misconception, to disappointment regarding how little his friend understands him, to suspicion regarding his brother’s role in all this, if Taichi is going so far as to raise these obviously untrue hypotheses.

When asked what he truly wants, Touma says he “wants to be free” – an understandable desire, given the course of his life so far. His brother worked hard to support him, and he doesn’t want to be a burden on him any longer, so him getting a job immediately would essentially free both of them. He’s tired of the expectations of baseball, and seems like he was partially engaging in the sport simply to have a clear direction and obvious way to excel, alongside allaying the questions of others regarding his feelings or ambitions. He wants to continue being close to Taichi, even though he assumes they’re as close as they’ll ever be, and having a local job would likely keep them together. He wants so much he can’t have, and so he takes control of what he can, cleaning the house and attempting to make his own way professionally.

When asked if he’s not free now, and if there’s anything he truly wants, we get another of those rare shots fully from his perspective, revealing Taichi just the way Touma sees him. But how can he share those feelings with Taichi, when Taichi’s just being his usual supportive self, and couldn’t possibly know how Touma feels? For both characters, this conversation is defined by an invisible wall they seem unable to circumvent

For now, Taichi’s support is enough. But looking down at their old board game after Taichi has left, Touma can’t help but reflect that there is no way to make everyone happy.

The story then turns back to Futaba, her entrance announced through the opening line of “I like flowers” set against a wide open composition, with only Futaba ultimately interrupting the frame. This technique creates a sense of stillness and silence, and naturally frames Futaba as an intruder, not wanting to take up space, but nonetheless accepting she will be an imposition. In the context of her family, we can see why she’d adopt this poise; she is talked around and disrespected, treated like a dependent or pet while she shrinks in the compositions, taking up as little space as possible. The flowers are gentle and quiet, like her; with her whole posture, she attempts to apologize for her presence, to be like them.

Futaba’s reflections at a bookstore emphasize the reciprocal positive feedback loop shared by her and Taichi. Neither of them believe themselves to be brave, but each is inspired by the bravery displayed by the other, which pushes them in turn to seek what they truly care about. While Touma sees Taichi as his beloved, comfortable past, Taichi and Futaba are pushing each other towards the future. It’s about the best thing a lover can offer you: a dizzying height to reach for, only to look aside and see you’re inspiring your lover to greater heights of their own.

Bumping into Touma, Futaba again demonstrates that she is both bolder and stronger than she realizes. As is frequently the case, she ends up leading from the rear, proving herself the anchor of these friendships as she suggests they hold a birthday party for Taichi, and all go to the fireworks festival together. Though she doesn’t believe in her own strength, she is often the first to break the ice, forcing herself to be brave rather than accept a polite misunderstanding or disagreement. And in her element, she shines like the brightest flower, happily bonding with Touma over their shared love of Taichi. Futaba is in fact so disarming that she prompts Touma to directly ask the question of “are you in love?” And presumably in a wildly misguided effort to break the tension, he clarifies himself, asking if she’s in love with Taichi or him.

It is very much in keeping with Blue Flag’s naturalistic, melodrama-averse storytelling that Touma would just accidentally pop the question as a joke here, and that the answer to that question would not be any sort of conclusion, but simply one more step along their mutual journey. Romantic drama doesn’t cease at the moment you admit to your feelings – that’s really more the starting point, the foundation from which something mutually meaningful can hopefully be constructed. Love is simple and pure as an abstraction, and far more complex as an actual commitment.

Confronted by Touma’s blunt question, Futaba runs through a rapid montage of her feelings for both of them. Piece by piece, these vignettes clearly demonstrate that while she admired Touma from afar, she loves the relationship Taichi and herself have built together, and she has a much fuller appreciation for every aspect of his personality. Futaba didn’t wish to be with Touma, she wished to be like Touma – to embody the courage he once offered her, when he told her that her best friend would always be herself, and thus she should try to be kinder to her best friend. A gentle piece of advice that impacted her profoundly, and which brought her to this moment of returning the favor. Reflecting on her “allowed range” of ambitions, Touma immediately sees himself in her words, struggling for the freedom to express his feelings for Taichi. And thus he arrives at his own fundamental question, asking “what kind of me do I want to be?”

Unfortunately, single emotional revelations cannot replace the slow, steady work of building self-confidence, of being kind enough to yourself to believe in the kindness shown by others. Thus, though Taichi has changed to an extent, he still can’t believe in his friends’ feelings towards him, and instead resentfully sees this whole fireworks expedition as a date between Touma and Futaba that he’s just awkwardly third wheeling. With their understanding of each other’s feelings so wildly out of step, it falls to Masumi to try and pair them up correctly, and of course she’s pretty much the last person you’d turn to for tactful, graceful resolutions of social conflicts. Thus the simple act of choosing who’s to go back for shaved ice becomes a game of love-couple musical chairs, with Touma suggesting Masumi join him, Masumi aggressively declining, and Futaba eventually volunteering to go, after which Masumi berates Touma for not taking that opportunity himself.

It’s all a mess of anxiety and missed signals framed around the allegedly natural, obvious romantic tropes of an event like the summer festival, and through that messiness it demonstrates again how high school romances are generally a kind of performance, their participants going through the motions they’ve internalized regarding intimacy and relationship development, and hoping to eventually come by those motions naturally. It’s an anxious charade, but that doesn’t make it any less real, or out of step with the rest of high school. Adolescence is by and large a period of faking it until you make it, performing the self you believe you want to become, and praying the insecurity of the act doesn’t leak through.

The hanging lanterns of the festival lead us away from Touma and Masumi, their lights guiding us on a path towards Taichi as tightly stacked panels announce the festival’s bustling main street. And on the next page, the balance of black and white does a similar job of clarifying the characters’ impression of the moment. Among a sea of tightly stacked and similarly thin-lined panels, the two focusing on Taichi’s pure-black strap stand out sharply, serving as a visual anchor for us just as they serve as a physical anchor for Futaba. Taichi may be gloomy, but he is her port in the storm – something she at last resolves to tell him, in a series of descending panels that tumble like fall leaves towards the ground.

The background fades away entirely as Futaba considers revealing the truth; nothing else is real in this moment except for Taichi, and what he might say to her confession. As the two pairs express their feelings to their confidants, we are gently carried from conversation to conversation both by the contrasting topics and the visual framing of the pages, with incomplete panel lines and pans to the sky frequently leading us from one field of battle to the other. Through contrasting Touma and Futaba’s thoughts on who they are, who they love, and who they want to become, Kaito draws an empathetic parallel between them, emphasizing how in spite of how lost, alone, and confused they feel, those feelings are universal, and nothing to be ashamed of.

Our leads’ cascading references to a “normal person” highlight their greatest point of commonality – their shared adolescent fear of bucking the trend, of failing to mature into a normal person. What they cannot understand, particularly not at their young age, is that every human being constructs their own sense of normal, and that the only thing that truly matters is that your “normal” promotes happiness for you and the people around you. Even Masumi shares this sentiment, wondering why she “must be so afraid of the prying eyes of others.” A fear with sensible, tangible heft in a heteronormative society, where expressing any sort of queer emotion risks not just rejection, but social censure and even personal harm.

For her part, Futaba is so determined to articulate her feelings regarding Touma that she accidentally lets slip how she actually feels about Taichi. In the heat of the moment, her tightly compartmentalized boxes of truth jumble and fall, one revelation tumbling into another as Masumi laments her own feelings, the sorrow and shame, the conflicting desire for Futaba to be happy and bitterness that Futaba’s happiness doesn’t include her. It is a painful moment, but also a poignant and beautiful one; as Touma stares at her, he sees the complexity and the glory of her true nature. Blue Flag’s heroes strive desperately to conceal their feelings, ashamed of what they truly desire, afraid of what their precious friends might say in response. But through Touma’s eyes, and captured by Kaito’s pen, it is made clear that there is nothing to be afraid of – that in these moments when we truly understand each other, we are most beautiful of all.

This article was made possible by reader support. Thank you all for all that you do.