Hello folks, and welcome back to Wrong Every Time. Today the thermostat is inching its way towards one hundred degrees, a balmy temperature for the infernal planes, but clearly unacceptable for us soft-skinned, hydration-fueled mortals. The heat is almost making summer’s encroaching end seem less miserable, but damnit, I am a summer season diehard, and if that means dying of heatstroke for my beliefs then so be it. Anyway, these unlivable temperatures have unsurprisingly facilitated plenty of film and show screenings – I’m actually just a half-dozen episodes off finishing Slayers TRY, and have munched through as many movies in the past week. Let’s break down a few of ‘em in the Week in Review!

First up this week was The Deadly Spawn, an ‘83 creature feature written and directed by Douglas McKeown, in essentially his only brush with the world of cinema. After a meteor lands near a rural town, strange tadpole-like creatures begin to emerge and terrorize the local populace. Trapped in their home by a violent storm, one family discovers their basement has become the nesting ground of these fast-evolving creatures, and will have to fight to survive against a rising tide of flesh-eating spawn.

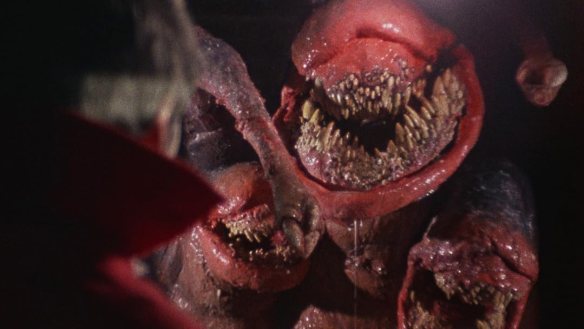

This one falls in the category of “how the hell did I not see this before,” as gooey, Tremors-adjacent creature features are easily one of my favorite indulgences. And The Deadly Spawn is a satisfying effort in all respects, particularly impressing with its distinctive, lovingly constructed monster, which falls somewhere between Biollante, the xenomorph, and Audrey Two. The film doesn’t skimp on the effects work for its kills, either – there’s plenty of nastiness here that demonstrates that fundamental truth, “the backbone of low-budget horror is the practical effects specialist.”

The human cast is also surprisingly likable; there’s a heroic younger brother who basically plays a dead ringer for Corey Feldman’s character in Friday Part 4 (released just a year after this film), and a group of old ladies whose bridge-party camaraderie is so endearing I almost felt disappointed when we got back to the horror shenanigans. I was even impressed by how the film made use of its central venue; with a basement and three floors to cover, the house makes for a dynamic evolving battlefield, with the spawn claiming each floor in turn like a flood or rising fire. A hidden gem in all respects.

I then screened Koyaanisqatsi, a quasi-documentary produced and directed by Godfrey Reggio, with a score by Phillip Glass. Named after a Hopi word for “life out of balance,” the film attempts to portray precisely that, contrasting images of the natural world with the excess and ultimate self-destruction of modern humanity. There are thus long sequences dedicated to clouds and canyons, plenty of time-lapse photography capturing New York City in motion, and ominous slow-motion documentations of exploding rockets and collapsing housing projects.

The film offers a compelling, intuitive sensory experience, building off of visual juxtapositions that feel as natural as Glass’ evolving score. I imagine some degree of its impact has been lost for me via repetition; these sorts of “humanity in aggregate” visual laments have become a general tool of cinematic language, employed in even such far-flung properties as End of Evangelion. But though the message is simple, the imagery is striking, and Glass’ contributions are unsurprisingly excellent. It’s definitely an experience worth encountering at some point.

I then checked out Wild Strawberries, a ‘57 Bergman feature centered on Professor Isak Borg (Victor Sjöström), an old man who is about to celebrate fifty years as a doctor with a ceremony at his old university. Afflicted by ominous dreams of death and isolation, he decides to make the trip to the university by car, accompanied by his son’s estranged wife Marianne (Ingrid Thulin). Along the way, he encounters a variety of characters that tease at his lingering anxieties, conjuring visions of childhood and ancient regrets.

Borg’s journey offers a poignant yet never sentimental examination of the cost of living your life according to your own sensibilities. Borg is a complex and difficult man, and Sjöström’s performance expands to fill every nook and cranny carved by his victories, failures, and lingering ambitions. As is generally the case with Bergman, characters say what they mean, or at least what they think they mean, far more often than our cagey real-world instincts would allow – but rather than simplifying their conflicts, this only further illustrates their endless contours, the truth each of them sees, and the pain that colors their visions.

Alongside offering a vivid psychological portrait and thoughtful reflection on the ambiguity of a “life well-lived,” Wild Strawberries is peppered with Bergman’s reliable wit; like The Seventh Seal, the film’s reputation belies its warm, even farcical humor, like in the bickering between two young men who have respectively sworn allegiance to god and science. Additionally, the imagery used for Borg’s nightmares often strays into absolute nightmare territory, combining shades of German impressionism with clear psychological undercurrents, demonstrating again how Bergman was, among his many accomplishments, undoubtedly one of the forefathers of cinematic psychological horror. As one of the most decorated films by one of the most celebrated filmmakers in history, I can now add my voice to the chorus declaring that yes, Wild Strawberries is very good.

I then went to check out Weapons, the followup to Barbarians from Whitest Kids You Know alum Zach Cregger. The film centers on the ordinary town of Maybrook, Pennsylvania, where one night at 2:17 in the morning, all of the children from teacher Justine Gandy’s third grade class got up, left their houses, and ran off into the night. With no evidence beyond the security cams capturing the children’s flight, and no “suspects” beyond Gandy and the lone unafflicted child Alex, the community are left to reckon with an impossible, inexplicable tragedy.

Cregger really latched onto a perfect image in that vision of children leaving their homes, charging lightly down the street with arms spread, like they’re heading off at the call of some nightmare beyond our imagination. Is there some instinct within them, some wisdom specific to a child’s mind that called them into the night? Are they fleeing something, or drifting into another world – and if we followed them, could we arrive there too? The evidence offers nothing – just small silhouettes dancing off into the suburban night, the underlying fear of this alleged secure, civilized world made manifest.

The film sadly can’t maintain the haunting allure of that core image, but how could it? And frankly, even if a director were to accomplish that feat, it wouldn’t be Cregger – that’s squarely in Picnic at Hanging Rock territory, the closest modern analogue of which is likely The Witch. Regardless, while Weapons’ ultimate revelations are less impactful than its premise, it still offers an engaging, satisfyingly winding spectacle.

As in Barbarian, Cregger excels at a specific horror-comedy tone where the frequent comedy beats never undercut the intensity of the drama. At times, he’ll jump from a gag to a horrible revelation and back again, finding a junction between the two in the at times farcical, at times grotesque absurdity of modern life. I also appreciated its general thematic ambiguity; at a time when lots of modern horror feels somewhat didactic, Weapons gestures towards issues like public trust or violence in schools without ever offering a pat moral lesson. That itself is the throughline which connects the film’s striking first images to its ambiguous conclusions – this world is darker than we know, and attempting to make moral sense of it will only leave you grasping at shadows.