Hello folks, and welcome back to Wrong Every Time. This week I concluded my journey through Slayers’ first three seasons, which I am led to understand is basically the conclusion of the “classic series,” barring some scattered film and OVA appearances. I’ll likely check out the film next (it was quite a surprise to learn the amply chested lady everyone loves doesn’t even appear in the main series), but in the meantime have since been munching through The Owl House, Dana Terrace’s entry in the post-Adventure Time western cartoon renaissance. The show is unsurprisingly delightful; I don’t know how Terrace got Disney to greenlight “lesbians hang out in the dreamscapes of Hieronymus Bosch,” but I am absolutely here for it. Anyway, films!

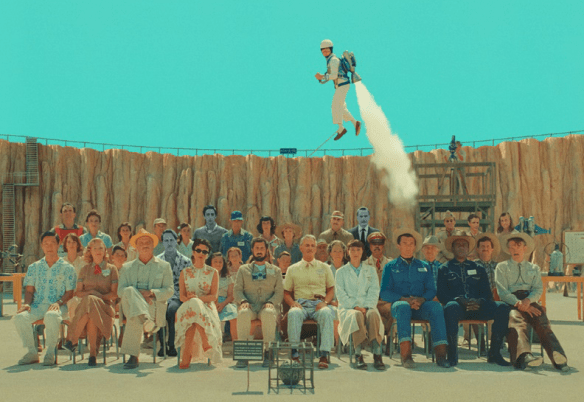

First up this week was Asteroid City, Wes Anderson’s recent film about a youth astronomy convention that is interrupted by the appearance of a genuine alien. A quarantine is swiftly called, leaving the convention’s honorees, their parents and families, the adjacent motel staff, a class of visiting elementary schoolers, several singing cowboys, and the local military to all get along as best they can while the crisis is handled. And of course, in typical Andersonian fashion, all of this takes place within the mid-century play “Asteroid City,” a production that is now the subject of this film’s documentary framing device.

As that description implies, Asteroid City is Anderson at his most ornate and precious, making dioramas within dioramas while Brian Cranston (one of the film’s many extravagant casting flourishes) gravely narrates the drama. Nonetheless, like most of Anderson’s films, there’s a human core here that all the artifice is genuinely working to elucidate, an internal story of grief, and an external story of the plight of creation, and how we attempt to find the meaning in fiction that we have such trouble finding in our own lives. It’s also quite beautiful; it feels like Anderson has always been seeking to make his live-action sets feel like his stop-motion ones, and Asteroid City’s candy-colored pastels and ostentatiously artificial motel cabins feel like his truest realization of that dream so far.

Unsurprisingly, the absurdly talented and largely Anderson-associated cast also do an excellent job, with the child actors actually stealing a good number of scenes (I think Anderson likes kids as much as Eggers clearly hates them). Jeffrey Wright continues to prove himself Anderson’s most essential new troupe member, and if Tom Hanks wants to come back for another, he is absolutely welcome. And the contrivance of the premise ultimately serves a key role, both in emphasizing the core themes of artistic longing and personal regret, and also clarifying Anderson’s own position within these struggles. There are two specific sequences that make it into the documentary but not the play itself – scenes the playwright cut for time or because they were too obvious, but which Anderson’s own sentimentality places as the lynchpins of the whole thing.

I then checked out The Legend of Boggy Creek, a ‘72 docudrama centered on the tiny town of Fouke, Arkansas, whose surrounding swamps are allegedly haunted by the Bigfoot-like “Fouke Monster.” Combining interviews with actual locals and reenactments of key encounters with the beast, director Charles Pierce crafts an impression of a community under siege from a strange, melancholy creature, while also realizing the singular beauty and isolation of the Arkansas backwoods.

I’m sure it’s no surprise that Boggy Creek earned one of my fastest awareness-to-screening ratios, as the film seemed as absolutely My Shit as anything could possibly be. And yep, Boggy Creek is an absolute delight, balancing gorgeous nature photography with ominous recollections of encounters with the beast, a creature beyond our understanding, yet just human enough to invite both pity and fear. Of the two, it is actually the first that most impresses here; salesman-turned-director Pierce’s visions of the Fouke swamps and woodlands are stunning, a procession of images that capture both the fierce beauty and ominous ambiguity of the untamed wilds.

The woods and bogs feel endless in Fouke county, too wild to comprehend, too enormous to contain. One comes to appreciate the fascination they hold for so many, and the joy these farmers, trappers, and outdoorsmen find in navigating their unfamiliar reaches, as distant from human contact as if they were on the moon. Some vignettes don’t even raise the specter of the monster, and the film is better for it, constructing a portrait of town and country as alluring as its gestures towards the great lonely beast that wanders its creeks. A singular, enchanting portrait of a town and its creature.

Our next viewing was Plane, a disaster-action feature starring Gerard Butler as the captain of a plane that goes down in a thunderstorm, forcing him to make a desperate landing on a remote island in the Philippines. Suspecting they are not alone on the island, he teams up with an alleged murderer being extradited to Canada (Mike Colter), and soon discovers an expansive criminal operation. With the rest of the passengers taken hostage, Butler will have to do what he does best in order to bring his companions home.

Plane is a tidy little feature that knows exactly what it’s about, wasting little time setting up its core variables, and exploiting mechanical hurdles like its blind-flying descent and jungle battlefields with distinction. The production is pure “film as videogame” indulgence, and Gerard Butler is one of cinema’s most reliable third-person action protagonists, moving his body in such a way that you believe in both his battle-tested physicality and wounded underlying soul. I can respect a film that knows exactly what it wants to be and unerringly pursues that target; if you’re looking for an action thriller with momentum and setpieces a’plenty, Plane is a fine choice.

Last up for the week was Bloodbeat, a thoroughly demented slasher that I feel will ruin my credibility just to describe properly. Nonetheless, here we go: the film centers on a girl named Sarah, who’s accompanying her boyfriend Ted to his rural home in Wisconsin. After fleeing from a family hunting expedition, she encounters a dying man in the woods, and later discovers a suit of samurai armor in the family home. Eventually, it becomes clear she has a psychic connection with the ghost of a samurai warrior, who manifests to kill people whenever she falls asleep or gets horny. Thus it falls to the psychically gifted members of her boyfriend’s family to stop her horny ghost samurai rampage.

Yep, that’s… that’s it. No embellishments made, some tangential story elements actually excised, and basically every bit of context regarding our psychic ghost samurai killer included. Apparently the “Bloodbeat” of the title actually references the powerful concoction of drugs that kept director Fabrice-Ange Zaphiratos’ head pounding all throughout production, and I do not doubt that is true. That said, I did sorta enjoy the bald-faced lunacy of the feature; its pieces don’t connect well enough to provoke any sense of genuine drama, and it basically loses its plot altogether in the second half, but “ghost samurai haunting the woods of Wisconsin” is hard to make entirely unwatchable. Also fun are Zaphiratos’ wild visual effects, ranging from a sort of ectoplasmic glow enveloping the samurai to a quasi-Predator vision used for his own perspective. Certainly not a good or even competent film, but also one strange enough that I’m quite happy it exists.