Twenty Years Later is the story of João Pedro Teixeira, a leader of Brazil’s rural Peasant Leagues who achieved some notoriety in the early 1960s. Teixeira was vying for more equitable conditions for his town of Sabe’s workers, who were being heinously exploited by the local landowners. Forced to produce cash crops for export instead of self-sustaining food, and constrained within a situation where both their jobs and homes were owned by local barons, Teixeira’s neighbors had no recourse but to come together, using the title of “Peasant League” to avoid the fraught term “union.” This semantic defense did not protect them; Teixeira was murdered on the side of the road while returning his son’s library books, and his league died with him.

However, Twenty Years Later is also the story of the late 20th century more generally – the story of capital crushing humanity, guided by the firm hand of the United States and the unfathomable callousness of Henry Kissinger. Director Eduardo Coutinho initially planned to tell Teixeria’s story in 1964, and even cast the man’s wife to play herself in his production. However, filming was soon halted by the rise of Brazil’s US-backed military dictatorship, which would maintain a brutal reign over the nation for the next two decades. It would take seventeen years for Coutinho to return to his project, and a full twenty before his film was finally released.

Combining footage from his original project with documentation of the survivors two decades on, Twenty Years Later thus proves a unique historical artifact, a documentation of a better world failing to be born, suspended between the bright, fiery hopes of its genesis and the ultimate unspooling of its ambitions. It is a tale of the optimism and solidarity that defined the most hopeful moments of the 20th century, and the profound callousness of capitalism in its quashing of those glimmering lights. It is, in its own specific, highly personal way, the story of how we failed to become better – how we were given a chance to reshape the world around mutual aid in the wake of kings and empires, and chose instead to remake our kings and empires in the form of landlords and corporations.

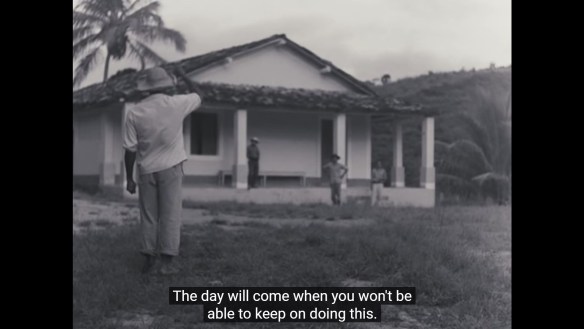

The contrast of early idealism and decades-on commentary makes for a poignant journey through the film’s first act, as Coutinho’s crew detail the mood in Brazil at the time their film was conceived. We hear that “images of poverty in contrast with imperialism were a typical tendency of the arts at those times” – an era of nascent revolution, now reduced to a footnote or cliche. After all, isn’t one great promise of art that injustice cannot stand up to the light of the sun, to documentation and revelation? Twenty Years Later does not need to editorialize; we can clearly feel the idealism of the young student filmmakers and righteousness of their cause, all of whom felt they were on the cusp of a new era, none of whom saw the following decades of subjugation coming. In one fragment of the original film, we hear their actors defiantly declare that “the day will come when you won’t be able to keep on doing this” – the frame then cuts, revealing the same building in both color and ruin, twenty years down the line.

It is enlightening to see this portrait of resistance strung laterally across time, yet at the same time, Twenty Years Later’s articulation of oppression feels distressingly familiar. Predatory rent hikes, forced labor without payment, eviction without compensation, the monopoly on state violence enjoyed by wealthy landowners… even if you set aside the still-relevant threat of assassination, all of these tools remain key facets of modern capitalism, and of our general relationship with our financial overlords. America’s last and possibly future president built his reputation on tools like rent hikes, denial of labor compensation, and land squatting. Everything that Twenty Years Later rallies against remain essential to capitalism, and are even seen by its conservative evangelists as icons of virility, intelligence, and strength.

For the small town of Sabe, these tools were harnessed to a grotesque extreme. The scale of injustice Teixeira was opposing is acutely realized through the example of the “village coffin,” a single coffin they would loan from the mayor for their dead, which they would send back after depositing the corpse in the cemetery. The denial of such a basic need seems inhumane, but in truth, it is merely an honest reflection of the landed classes’ eternal goals. Our overseers would deny us everything if they could, would leave us to starve if possible, as the advent of automation and AI have made abundantly clear. The boss will always be our enemy, always attempt to extract everything he can for as little as possible, for allegiance to capital outweighs allegiance to humanity. As long as there are owners and there are workers, this struggle against the greed of the overseer will always be our only route to safety and justice.

Even though their quest is doomed to failure, there is a vitality in Teixeira’s struggle, a hope borne of the pure simplicity of seeing the world labeled for what it truly is. The true story of capital’s victory over humanity is so obvious, straightforward, and malicious that it can drive one mad seeing how completely our culture ignores it. Perhaps we accept this situation as normal or just because we simply have no alternative. Even these workers could fight back, as revolutionaries have done throughout history, but the might of American empire in the face of our scattered resistance just seems utterly implacable, so we might as well give up from the start, and make peace with the cruelty of this system. So it goes for the rebels of Sabe and Galilea, who scatter in the wake of Teixeira’s assassination.

Twenty years on, only two of the men who began the fight alongside Teixeira are still alive. The recounting of their and their allies’ fates is Twenty Years Later at its most callous and clear – once would-be heroes and cinematic revolutionaries now chastened and isolated, making due with what work they can find, or giving themselves over to Jesus. “Braz is disillusioned with political activity, and no longer like Galilea or remembering the past,” our narrator plainly states of one former actor. Another actor named Cicero has moved south for iron rolling work, and proudly states that “no one gets mad at me, not even the boss.” Cicero always hoped the film crew would return to finish their work, which his mother mocked as starry-eyed idealism. In the end, they were both correct: the film crew indeed returned, but too late for his mother to ever see it.

And then there is Elizabeth, the proud wife of Teixeira and mother to his twelve children. Forced into hiding for seventeen years, her reemergence and attempts to reconnect with her children guide the drama of Twenty Years Later’s back half. She is hopeful but chastened, praising the final military-imposed President Figueiredo for his slacking of the regime’s regulations, a choice that may yet allow her to see her family again. Her son is less forgiving; “all regimes are the same if you don’t have political protection,” he states, and furthermore asserts that Elizabeth survived not because of charity, but because she had no power worth taking. Elizabeth ready to claim what joy might still be salvaged in defeat, her son defiant in the face of corrupt paternalism; their perspectives align as he bitterly states that “no system helps the poor,” to which Elizabeth offers an instinctual, conciliatory “nope.”

Elizabeth is not alone in seeking peace. Having fought so hard and been so savagely chastened, the stories of many of these would-be revolutionaries is not about the endurance of strength, but about the eventual, fatigued acquiescence to power that is often our only option. Their lead actor Joao Mariano now serves as the leader of a Baptist church, saying “I’ve got my bit. I live without meddling with A or B.” Anyone who can get by without political agitation will generally do so; the risks are simply too high if you have anything left to lose. Fellow survivor Joao Virginio puts it more sharply: “I was blinded in one eye. I lost hearing in one ear. Then my heart went. I spent six years in jail. What good did I do for Brazil behind bars?” With such extreme measures taken in the face of such basic resistance, it is easy to understand why most simply give up, and find a way to live quietly within modern wage slavery. “Call that revolution?” Virginio bitterly reflects. “Put me in jail, my kids left hungry?”

A persistent refrain, shared by Mariano, Virginio, and many other survivors, is to ultimately trust in God. “I trust in God, because this misery…” Virginio stares across the plain before continuing, either collecting his thoughts or willing himself to believe them. “One day, the people got to realize who they are. We can’t stay trampled on forever.” When no one else will help you, what other hope can we cling to but the divine, the prayer that salvation will ultimately come to those who wait?

What true hope of solidarity can be found is often seen only in the margins, in the echoes of past conflicts, or the small acts of charity that allow Elizabeth’s family to endure. Joao Jose, the son of one would-be revolutionary, eagerly explains how he implemented a system to ensure the military could never steal his precious books. He reads from the dedication of Curzio Malaparte’s Kaputt, “I will always be grateful to the peasant Roman Suchena and his daughter-in-law for helping me to save my manuscript from the hands of the Gestapo” – another link in this fragile, precious chain of collaboration and resistance in the face of unspeakable evil. Twenty Years Later serves as its own link in the chain, demonstrating how capitalists may steal our homes and even our lives, but with pen or camera in hand, they can only steal our histories, our truths, if we let them.

In the meantime, we find what happiness we can in the spaces that are afforded to us. Elizabeth’s nascent reunion embodies this hope, as one child after another is informed of her intent to reconnect with the family. The revolution failed, but this hope remains – not that our bravery and compassion are rewarded with triumphant change, but that we might nonetheless weather the storm with grace, and one day emerge into a brighter world still clinging to the ones we love.

The town Elizabeth escaped to is not free from capital’s clutches. The song remains the same; the dying town of St. Rafael will soon be destroyed to create a dam, and with no deeds securing their land, the current inhabitants are due to receive only meager compensation. Though busy with her own concerns, Elizabeth enjoys discussing union activities with local leaders, advising them on how to deal with the many heads of the snake. “The fight goes on. The same needs as in 1964 are still with us. They haven’t budged.” And yet, somehow, neither has Elizabeth. Even as the camera crew make their goodbyes and pack into their van, Elizabeth is still preaching the good word: “The workman, the peasant, the student all have the same needs. The fight goes on while there is hunger and poor wages. Who wouldn’t fight for better days? You must fight. We must fight while this so-called democracy, this hunger exists.” Her voice rings out, clear and defiant still as the car pulls away.

This article was made possible by reader support. Thank you all for all that you do.