Hello folks, and welcome back to Wrong Every Time. Today I write to you from the midst of another cold, gloomy December day, as I wonder to myself why exactly we choose to end the year at the conclusion of such a miserable month. How are we supposed to feel optimistic about the new year at the end of fuckin’ December, when the cold’s already seeped deep into our bones, and the promise of spring is still several brutal months away? I’d frankly prefer it if we were continuously running through an April-to-September circuit, with no threat of frigid weather looming over us, and the promise of a fresh summer never more than a couple months away. Of course, I’d miss Halloween, but perhaps we could just push that back a month and have it serve as September’s end – I mean, it’s not like September’s got anything else to do with its time.

Anyway, where were we? Ah yes, the Week in Review. Let’s break down some films!

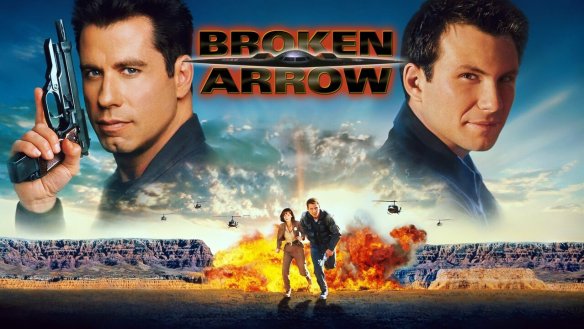

First up this week was Broken Arrow, a ‘90s John Woo feature starring Christian Slater and John Travolta as air force pilots tasked with flying two nukes on a stealth exercise across the midwest. However, after attacking his copilot mid-flight, it soon becomes obvious that Travolta plans to use the nukes as leverage in order to extract a ransom from the government. With only a local park ranger to support him, Slater will need to hunt down Travolta’s party and recover the nukes, or risk bathing the region in nuclear radiation.

Released three years after his American breakthrough Hard Target, and just a year before the incomparable Face/Off, Broken Arrow sees Woo in confident command of an eminently ‘90s style of Hollywood action, the sort of tangentially political action-thrillers typified by films like Air Force One or Clear and Present Danger. It’s also his first collaboration with John Travolta, whose maximalist, gleefully cartoonish approach to villainy would prove a perfect fit for Woo’s own theatrical style. It’s no wonder that Face/Off has become such an enduring favorite – Woo is one of the only directors whose style matches Travolta and Cage at their most untethered, echoing through swooshing camera movements and exuberant fight choreography the strained muscles and bulging eyes of Hollywood’s most kabuki-appreciative leading men.

Travolta is clearly the star here, with Slater’s lukewarm charisma and dubious chemistry with heroine Samantha Mathis proving incapable of similarly commanding the screen. Fortunately, while the film’s interchangeable desert vistas and lack of scene-to-scene propulsion sap it of some energy, there are still enough dynamically constructed action setpieces (helicopter battle! Humvee chase! Train heist!) to keep things engaging, and Travolta maintains that delightfully manic enthusiasm from first to last. An inessential Woo (try Hard Boiled or A Better Tomorrow if you want to see him at his best), but not an unwelcome one.

Next up was Thanksgiving, Eli Roth’s full-length expansion of the holiday-themed slasher he teased during the faux-trailers accompanying Tarantino and Rodriguez’s Grindhouse. After a Thanksgiving day pre-Black Friday sale results in a shopper stampede and several deaths, the film sets us down one year later, with the kids who accidentally instigated the riot now in the crosshairs of some violent avenger. As the various guilty parties are murdered in a variety of gruesome ways, the remaining survivors will have to join together and hunt down the killer, or risk becoming the latest items on the menu.

Honestly, I’m mostly just surprised this movie wasn’t produced before now. No, you know what, I get it – traditional slashers were pretty out of fashion at the time Grindhouse was released, with even self-aware slasher riffs like Scream starting to lose their steam. This was the era of Saw and Hostel, films that dispensed with the suburban setups and inherent camp of slashers to provide raw, ugly violence with no filter or breathing room. It was a dark time for the genre, to be honest.

Well, we’ve now reemerged into the glorious sunlight of slasher revivals, which fit comfortably alongside this era’s so-called “prestige horror” features to furnish an altogether healthy horror movie ecosystem. As such, there is again market demand for a gleeful throwback like Thanksgiving, which offers a distinctive masked killer, a variety of red herrings, and a collection of inventively nasty death scenes. Great use of industrial saws and ovens in this one, and I can assume your reaction to the film at large will entirely rest on whether that sounds exciting or revolting to you.

We then journeyed onward to Ong-Bak 3, which concludes the historical fantasy drama begun by its predecessor. While this sequel dispenses with the tangled narrative rambling that drained its predecessor of dramatic momentum, it is unfortunately no more effective as a film. Stripped of Ong-Bak 2’s betrayals and counter-betrayals, it becomes all the more clear that the film’s fundamental structure isn’t really functional. There is no connective tissue here; simply a procession of “why don’t we try this idea” swerves, buttressed with flourishes of dazzling fight choreography.

After spending the proceeding film attempting to get revenge on Lord Rajasena, the killer of both his original and adopted families, Tony Jaa opens this film in chains, staring up in fury at his hated oppressor. His bones are broken and body crippled, ultimately forcing him to spend the first half of the film recuperating and learning to incorporate fluidity into his combat style. At last, he gains the strength necessary to defeat his nemesis – only to learn that Rajasena was actually already defeated elsewhere, by a mystical fighter Jaa was only briefly acquainted with. Ong-Bak 3 thereby severs its own head prior to the climax, robbing both Jaa and the audience of this trilogy’s obvious intended conclusion, and replacing it with a battle that presumably must have sounded cooler during script revisions. The end result is as clumsy as it sounds, leaving this trilogy as one great film followed by two bloated, unfocused escapades with undeniably great fight scenes.

I concluded the week by following up my viewing of the original Trigun series with Trigun: Badlands Rumble, a 2010 Madhouse production helmed by original series director Satoshi Nishimura. The film offers a standalone adventure featuring all the original main characters, as Vash is forced to contend with the twenty-year grudge of outlaw Gasback. Cities will be threatened, guns will be blasted, and Vash will inevitably teach everyone a valuable lesson about violence or friendship or something.

Trigun is a natural choice for this sort of film-length supplementary arc, as even the original series’ drama was mostly a series of episodic wild west fables with melancholy moral takeaways. And it’s also quite nice to see these characters realized in such fluid animation, though to be entirely honest, I actually preferred the tactile grime of the original series’ cel animation, where even the limitations of the animation felt like a meaningful contribution to the show’s battle-worn aesthetic. But Badlands Rumble’s main limitation is unfortunately its plot; outlaw Gasback is an entirely one-note, wholly unsympathetic character, meaning this film’s story is actually less fully realized or emotionally resonant than many of the original’s twenty minute escapades.

This is not to say that the original Trigun was a repository of insightful moral questions, but it was at least trying, constructing ambiguous dynamics and family dramas that forced Vash to question who was truly in the right. Sadly, Gasback’s entire motivation is “my crew betrayed me because they wanted to actually make money from heists, rather than heisting purely for the love of the game,” and this is the motivation that is supposed to drive an entire film’s worth of resentment, revenge, and ultimate reconciliation with the daughter he abandoned. Trigun’s special sauce is its ability to conjure genuine melancholy regarding the inevitability of conflict and tragedy of our violent nature – absent an antagonist who in any way supports such a reading, Badlands Rumble is ultimately no more than a rotating track of yelling and gunfire.