Late in Chainsaw Man’s fifth volume, Denji and Aki are each presented with a brief parable, the story of the country and the city mouse. “The country mouse gets to live in safety,” they are told, “but doesn’t get to eat delicious food like they have in the city.” On the other hand, “the town mouse gets to eat delicious food, but runs a higher risk of getting killed by humans or cats.” It’s a dichotomy so simple it could apply to almost anything: risk versus reward, stasis versus progress, or the more obviously applicable choice between living in Makima’s devil-haunted world versus running with all your might. Of course, in order to fear the city enough to desire the country, you first require something to lose.

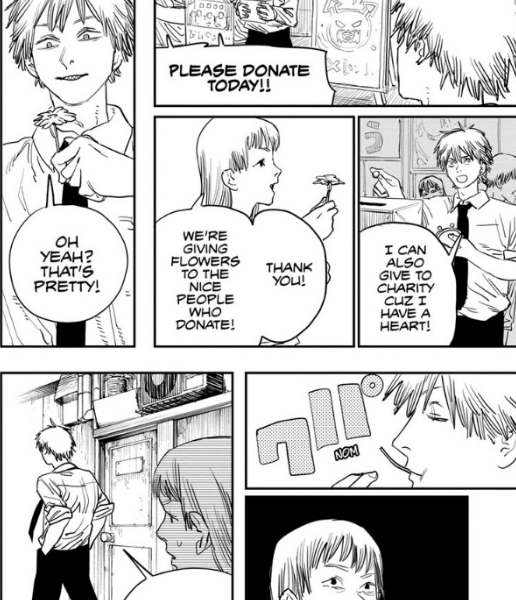

This question arrives in the wake of a great personal victory for Denji, having been assured by Makima that he does indeed have a heart. Strolling the streets with a smile on his face, he proudly announces his ability to give to charity and admire flowers, the clear markers of his underlying humanity (even if he’s not sure what to do with a flower except immediately swallow it). Denji is accustomed to thumbing his nose at high-minded concepts like “compassion” or “humanity,” which is no surprise – after all, such words are usually just employed to justify more work and suffering. But that doesn’t mean he also doesn’t yearn for love and understanding, to be recognized as a human being with a beating heart. And then, taking shelter from a sudden shower in an ATM stand, he runs into a girl who seems as desperate to love him as he is to be loved: the beaming, mysterious Reze.

A girl who finds him mysterious and interesting. A girl who laughs at his jokes. A girl who doesn’t seem to want anything from him, beyond his continued presence in her life. Denji’s first encounters with Reze proceed like a dream of normalcy, reflecting Fujimoto’s clear breadth of genre proficiency. Makima’s fascination with film obviously extends to Fujimoto as well; their encounters skip and whirl with the playfulness of Godard, the stark immediacy of Cassavetes. And in the grand tradition of basically any genre outside of shonen manga, things are allowed to just happen here, Denji and Reze’s mutual fascination swiftly progressing from coffee shop dates to late-night skinny dipping. There is no preamble to infatuation; these two clearly like each other, and their intimacy develops as swiftly as Fujimoto’s prior illustration of Himeno and Aki’s bond. As ever, Chainsaw Man feels no compulsion to foreshadow or tread water; narrative reliability can be a comfort to some, but in Chainsaw Man as in reality, life comes at you fast.

Here in the company of an ostensibly ordinary teenager, both the absurdity of Denji’s position and the blinders limiting his ambitions are made painfully clear. Why shouldn’t Denji enjoy mundane happiness, going to school and falling in love and wasting time with his friends? When Denji proudly explains the “luxuries” afforded by his Devil Hunter position, Reze immediately replies that his amenities are essentially subsistence living, the bare minimum required for survival. Denji is not living in some fantasy world where devil hunting is a standard early-teens career path; he lives in our world, and his preposterous situation reflects the profound level of exploitation our children are becoming increasingly accustomed to. Flipping shonen’s usual fantasy of “children embracing strength and adult-like independence” on its head, Chainsaw Man instead asks “why must we rely on the sacrifices of children to maintain our society?”

It is at this point, having challenged his impoverished aspirations and shared with him the simple joy of learning to swim, that Reze (and the Angel Devil) offers him (and Aki) the story of the country and city mouse. The Angel Devil and Reze both understand the sanctity and beauty of life, and would prefer to maintain it in the country. But Denji hasn’t learned to value his life so highly – how could he, given how easily it could be stripped away? Reze embodies an escape from the fragility of his current circumstances, a potential route to the slow, reliable pleasures of ordinary life. A road towards seeing life as precious, and thus worth protecting even if that protection demands a more gentle, conservative approach. And for the moment, it seems like Reze might see the opposite in Denji – chaos and excitement, a boy who’ll fill her world with unexpected new adventures.

Unfortunately, neither Angel nor Reze are entirely sincere in their proposition. Angel has already accepted there is no escape for him; bound by Makima and unable to flee to the country, he has decided that he’d “rather die than work,” and is simply waiting for a convenient exit. And as Reze chokes the life out of a would-be assassin, we learn that she is actually “the cheese used to lure the mouse out into the open,” a servant bound to the Gun Devil as tightly as Angel is bound to Makima. If anything is different about Reze, it is that she is a subtler manipulator than Makima – while Makima goes straight for Denji’s immediate, stated desires, Reze toys with his subconscious needs, illuminating a path towards a future characterized by dignity and mutual concern. In our world, such promises are rarely a genuine escape, and more often simply the product of smarter advertisers more closely attuned to our emotional needs, more graceful in their ability to harness our desire for happiness and freedom to mechanical, wealth-generating ends.

Of course, Reze’s behavior isn’t all that different from Denji’s own philosophy. He too is bound by his employment under a terrifying overlord, gravitating towards what feels good, generally not considering the moral consequences of his actions. Reze’s behavior is no different from the things Aki is constantly scolding Denji for – though she speaks of freedom and the joys of mundane life, she is in truth no more free than Denji, or truly any more contemptible. More alike than they know, their courtship passes as a literal blur, the diverse distractions of a festival swirling past and becoming indistinct. Only sharp, tactile moments like Denji’s figure brushing the goldfish tank stick out; in Fujimoto’s hands, their date blooms with the soft focus and warm bokeh accompanying cinematic moments of joy and release.

Given our knowledge of Reze’s true objective, her ultimate proposal to run away with Denji feels all the more tragic. Here is the mythical movie romance he’s longed for, now just another tool employed to recruit and exploit him. Is there anything like genuine, earnest concern and companionship in this world? Maybe, perhaps – but if so, it is only the solidarity between workers, the collective suffering of the downtrodden made a common currency of conviction and regret. Salvation will never come from above, it will only come from the oppressed collectively rising – which is precisely why Fujimoto keeps his perspective down in the dirt, where any would-be heroes like Denji or Reze are chained to their daily labors.

In a world such as this, even the hapless Denji understands Reze’s proposal is too good to be true. It shouldn’t be, of course – a base assumption of security and independence should be achievable for anyone, the bare minimum society should offer us. But everything Denji has experienced tells him to doubt this offer, and what’s more, he now actually does have something to lose. He’s achieved success and a degree of independence within his work, and thus arrived in a fresh new cage: the prison of investment in your own meager advances, a cage trapping countless would-be opponents of the status quo. The beautiful sequence of Denji and Reze kissing in silhouette embodies the sickness of Denji’s life; a cinema-ready moment that should be enjoyed without question or doubt, here defined by Denji’s preceding rejection and Reze’s ensuing betrayal. For with a crunch of teeth on tongue, it is here that Reze reveals her identity as the Bomb Devil.

Reze’s Bomb Devil form is perhaps Fujimoto’s most impressive design to date; a head somewhere between a blockbuster and a shark, a dress of woven TNT, a face that is implacable, nothing but black veneer and teeth. Her design and introductory pose evoke religious iconography, emphasizing how devils are essentially modern objects of worship. For fear is indeed a form of worship, the shadow cast by our hopes and aspirations. In modern society, we have largely moved past a collective belief in a higher power that works to redeem or protect us – all we have are the gods of Chainsaw Man, gods of cruelty and violence and despair, whose great works are undeniable in our fallen world. Gods are not deities we turn to in our moments of weakness, begging for succor or relief. Gods are cruel and indifferent creatures, their overwhelming presence emphasizing the certainty of suffering in a world where anything systemic, anything distributed from a central overseer, is undoubtedly bound to be a terrible affliction.

Of course, as everyone we know in the Devil Hunter division would attest, working for a malevolent overlord does not necessarily mean you share their values. Many are simply chained within a system that doesn’t allow for ethical labor, leaving only the barest opportunities for even simple decency or kindness. And those who are actually committed to these causes are often more deluded than malicious, as Aki is swift to demonstrate. Through his fond banter with old Division 2 compatriots, we are reminded again how his pursuit of the Gun Devil is not necessarily noble or enlightened, but ultimately just self-destructive. Finding happiness in this world is a rare, precious thing – if you have the chance to seek it, it would be beyond foolishness to throw it away. Fujimoto sympathizes deeply with those who find it too difficult to push back against their circumstances; all of us are just trying to find a slice of security and company who appreciate us, and he wouldn’t blame anyone for embracing that victory, rather than seeking to change the whole world order.

And so the battle continues, Reze’s rampage offering Chainsaw Man’s most viscerally thrilling sequence so far. Fujimoto’s articulation of her implacable pursuit makes it clear that he could easily helm a full-on horror manga – but frankly, I greatly prefer his tendency to touch lightly on genres, rather than embracing all of their embedded assumptions. Fujimoto infuses action, romance, and even comedy with flourishes of outrageous horror, emphasizing how the alleged boundary lines between these genres and tones is actually porous and thin. Our own lives are sprinkled with unexpected moments of stomach-turning dread – why shouldn’t our stories? In fact, by setting these horrors so adjacent to the mundane or uplifting moments of Denji’s life, Fujimoto makes them all the more impactful and terrible – for if we expect horror, we are less wounded by it when it inevitably arrives. More profound is when horror steals something, when it intrudes where it is not invited, rocking our sense of security in the process.

In this way, Fujimoto continues to thread the needle of entertainment without endorsement, using horror to ensure his violence never feels glorious or validating. The Bomb Devil is a figure glimpsed ahead on the road, something aberrant and terrible, lacking even a face to which we might assign motive or intent. When this creature tells them to hand Denji over, we know it really could kill everyone we’ve come to know without a moment’s hesitation. Aki wouldn’t “unlock a new store of power” to defeat it, Denji wouldn’t suddenly be empowered by the love of his friends – they would simply die, and that would be that. Action-focused stories frequently carry with them a certain unspoken faith that might actually could make right – or rather, that the most righteous among us ultimately also possess the greatest power. But anyone can hold a gun, anyone can take a life, and in the world of Chainsaw Man, violence is no more sensical or righteous than that.

It seems appropriate then, that this battle ends not with a triumphant victory, but with a tragic sacrifice. Can a shared experience of suffering be enough to unite us, to save us? As Aki sacrifices yet another segment of his life to save Angel, we simply have to believe it is so. Like Himeno before him, Aki doesn’t want to lose another partner, and will always risk his own life to save the people around him. Even if Angel doesn’t believe his life has value, he does not have control over the feelings of others – he cannot force Aki to similarly not care if he lives or dies. And Aki, in his characteristically curmudgeonly way, frames even his selflessness as selfishness: “if you want to die, do it somewhere far away from me.” The unwilling city mouse lives to fight another day.

Denji’s victory over Reze is similarly lacking in catharsis; it is simply tragic, their mutual sinking in the ocean serving as a reminder of Reze’s prior lessons, of the closeness these combatants briefly shared. Even if Reze was being dishonest, that moment of learning to swim with her was precious to Denji, something unique and irreplaceable and beautiful in memory. Can we only achieve genuine closeness bound together like this, seeking mutual destruction even as our bodies touch? Can there be an intimacy unmediated by capitalism, where we converge simply because we desire each other, desire to give of ourselves freely, to share the joy and love we feel in each other’s presence? Or can we only glimpse such happiness in parody, in this violent facsimile of genuine intimacy?

Perhaps I am looking at this the wrong way. Perhaps we can only achieve true, earnest intimacy by charging through the artifice, by admitting all of our interactions are loaded with a thousand different expectations and regrets, but still committing to them anyway. Perhaps there is a great wisdom in Denji’s perspective, as he acknowledges Reze’s crimes, understands the consequences of his choices, and at this point declares his desire to run away with her. Nothing is perfect, nothing is entirely honest, but perhaps we can accept that, and seek whatever joy we can find in our dishonest, transactional, yet undeniably human interactions.

Though Reze calls Denji a fool, she cannot deny the hope he represents. In spite of emerging from a childhood even more impoverished than Denji’s, she chooses to skip her train out to the country, and share a fragile city life with her new friend. But Makima has a different ending in mind. In an alley on the road to that treasured cafe, she tells Reze that she also likes the country, but only because she enjoys watching the suffering of the rats every harvest season. Her point is clear: whether you live fast or slow, your life is not your own, and your fate will be decided by the heartless beings who hang perpetually overhead. Even if Reze had actually taken the train, even if she hadn’t been fully charmed by Denji’s earnest affection, there was never any escape from this life for her. Happiness and escape are a beautiful dream, but also a fleeting one – in the end, this is still a world ruled by people like Makima.

And so Denji is left right where he started, alone again, eating a flower just so he can claim its beauty before someone steals it. He is human, he likes flowers, and he is indeed deserving of love. A pity this world is too callous to offer it.

This article was made possible by reader support. Thank you all for all that you do.