Hello folks, and welcome back to Wrong Every Time. It’s been another productive week on my end, as I’ve reduced my outstanding Current Projects to less than a dozen essays and other features, with my article buffer now encompassing more than a month’s worth of drafts. I’ve matched that productivity with a fair portion of off-the-books anime viewing, as we munched through more of Gundam’s supplementary Universal Century projects, as well as anime films both venerable and vestigial. Having watched so many of the early Toei films, I’m now looking to round out my ‘80s animation education, while also likely taking a break from Gundam to watch some other outstanding series; I haven’t quite decided yet, but Nadia, Mononoke, VOTOMS, and Moribito are all high on my list. Anyway, I’ll catch you all up on that when I get to it, but for now let’s break down my latest animated escapades!

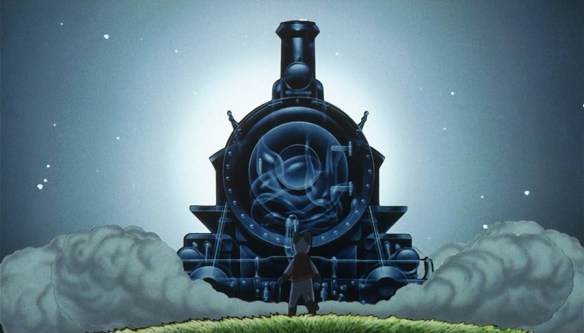

First up this week was Night on the Galactic Railroad, one of the key outstanding films in my classic anime education. Based on the beloved fantasy novel by Kenji Miyazawa, the film centers on the young and lonely Giovanni, who is bullied at school for his suspiciously absent father. His only friend is the quiet Campanella – and on the night of the Centaurus Festival, the two embark on a wondrous journey, riding the spectral galactic railroad to the end of the Milky Way.

Night on the Galactic Railroad is somber and dreamlike, poignant and peaceful, reserved in its script yet sprawling in its imagination. It proceeds not as a traditional narrative, but as a mournful travelog, offering anecdotes from fellow travelers and visions of fantastical scenery as our two leads travel among and beyond the stars. The only active progression is one of understanding; over time, Giovanni comes to recognize the true nature of this train he is riding, and the significance of his “very special” ticket.

In its vignette-based structure and loose philosophical questions, as well as its majestic imagery and melancholy tone, Night on the Galactic Railroad calls to mind Mamoru Oshii’s best productions, and clearly served as an influence on Spirited Away’s own train sequence. The film’s simplified, often geometrically incoherent architecture harkens towards my beloved Giorgio de Chirico, while its vignettes range from strange tales of skyfishing to recollections of ships breaking on ice, each new character pointing in their own way towards the mercurial form of a life well-lived. It’s the kind of film one feels they could truly live within, sinking into the padded seats of the cabin and letting the stars go by. But as the film consistently assures, all such journeys end too soon, making it all the more vital that we find our own stories to tell while we can.

We then continued our journey through the One Piece films with their fourth independent journey, One Piece: Dead End Adventure. This is actually the first of the One Piece films to embrace a full movie length, though it tragically can’t match up to the standard set by the impressive Clockwork Island Adventure. Fortunately, it’s got a punchy pitch to make up for it: the Straw Hats must compete in a no-holds-barred pirate race, vying to be the first arrivals at a dangerous distant island.

It’s honestly never a bad time joining the Straw Hats on these incidental escapades, and at this point we’ve even got Robin filling out the crew, which is always a plus. That said, in spite of this actually being the third One Piece film that was animated digitally, its implementation feels uniquely clumsy here, echoing the unfortunate smudgy look that undercut productions like Haibane Renmei. That, plus the fact that the sea race concept is abandoned only a few scenes after it commences, make Dead End Adventure fall on the lesser end of bonus One Piece escapades. An easy but totally inessential watch.

Alongside all of our film viewings, we’ve continued to march through the vast proliferation of Gundam properties produced over the last half-century, this time checking out Mobile Suit Gundam 0083: Stardust Memory. This thirteen episode OVA series slots in between the original Gundam and Zeta, offering both an independent drama of its own and a flourish of connective tissue aligning the first two series. The story concerns the hijacking of a nuclear-equipped experimental Gundam, which is pursued by a young pilot wielding the Gundam’s sister ship (Kou Uraki), as well as the prototypes’ designer Nina Purpleton.

With a non-Newtype, entirely mundane soldier as its lead, a frontlined romance between Uraki and Nina, and character designs by Bones co-founder and Cowboy Bebop character designer Toshiro Kawamoto, Stardust Memory bears quite a few resemblances to the later 08th MS Team. This is very much a good thing; having watched the majority of the Universal Century’s various productions, I tend to find the stories are stronger when they stray further from the fantastical potential of the Newtypes, offering sympathetic, relatable human dramas. And as an OVA series produced at the tail end of the bubble years, Stardust Memory is further furnished with absurdly luxurious animation, standing as one of the most visually compelling entries in the franchise as a whole. This one can stand proudly alongside 08th MS Team and War in the Pocket; far enough from Tomino’s style to chart its own path, close enough to his world-weary perspective for its punches to land with impact.

We followed that up with one of the most recent Gundam installments, the seven-segment Gundam Unicorn. Unicorn picks up several years after Char’s Counterattack, following Zeon’s final living remnant Mineva as she seeks the mystery of “Laplace’s Box,” a relic of the Universal Century’s birth that is said to hold the keys to humanity’s future. Along the way, she ends up befriending would-be pilot Banagher Links, a spacenoid who seems to embody the furthest reaches of Newtype potential.

It’s an odd thing; Unicorn came out twenty-five years after Char’s Counterattack, but watching this series actually helped me come to peace with Char’s prior decisions. Having trudged through two hundred-odd episodes of endless Universal Century conflict, it felt that much easier to now understand Char’s profound fatigue, the fatalism that led him to abandon all hope of humanity peacefully evacuating the earth sphere. And with a touch more distance between me and the indulgences of Double Zeta, I was also more appreciative of the counterpoint raised by the Newtypes – the underlying significance of their seemingly simplistic ethos, and how they embody through the pain of empathy perhaps the only escape from an eternity of war.

Anyway, philosophy of Gundam aside, Unicorn is also simply an action-packed adventure, a MacGuffin chase that is only occasionally undercut by its convoluted political backdrop and somewhat arbitrary objective. Old favorites like Char and Bright get to strut their stuff overseeing a new generation of pilots, and though there is some noticeable implementation of CG, it is accompanied by an impressive bounty of traditional mechanical animation. I can understand why people might find perpetual reprises of the Universal Century’s drama fatiguing, but frankly, I’ll accept that bargain if it means we still get stories that actually talk about war and generational inheritance with anything approaching a mature perspective. So long as Gundam flies that flag, I will continue to salute it gladly.