Hello folks, and welcome back to Wrong Every Time. Today I write to you amidst a frenzy of creative passion, as both the Evangelion writeups and new DnD projects are flowing abundantly. With our current campaign briefly on hold, my playing party just concluded a two-part post-campaign adventure in the world I created for our last campaign, this time both designed and led by one of our other players. The experience offered a refreshing perspective on campaign and narrative design; I am a creative-first top-down designer, meaning I essentially write a drama and then set to work translating it into DnD’s mechanical structures, whereas this two-parter’s designer is a mechanics-first, bottom-up designer, meaning he designs an interesting mechanical puzzle and then finds a creative coat of paint for it.

It was interesting to see how that mindset incurred various second-order effects in terms of how the sessions played out, and it’s also got me hungry to run my own adventures again. It is a wonderful feeling to have run a campaign that my players are clamoring to return to, and once I’ve concluded this Eva era, I’ll be eager to share some of my design documents with all of you. In the meantime, we’ve got a fresh pile of films to explore, so let’s get to work!

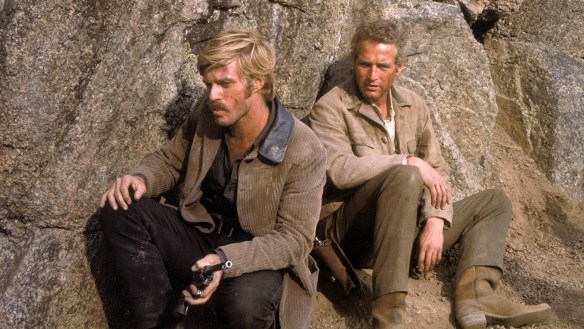

First up this week was Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a film which can easily be summed up as “Robert Redford and Paul Newman’s cowboy variety hour.” Though the film is handsomely shot and smartly structured and wittily scripted, its obvious raison d’etre is to luxuriate in the unfathomable chemistry shared by Redford and Newman. The pair count as one of the most convincing on-screen portrayals of best friends I’ve seen, cracking wise and busting each other’s chops and generally evincing an absolute willingness to die for each other with their every word and gesture. It worked for The Sting, and it works here – put Redford and Newman together, and magic is bound to happen.

The film wisely begins with the pair already well-established, letting us enjoy their easy friendship from the first scene, and also positioning Butch Cassidy within the lineage of “wild age in decline” films that typify maybe a third of all cowboy dramas. The pair’s first heist goes terribly wrong, and much of the film is dedicated to our heroes fleeing, hiding, and being forced to flee some more. With a less genial cast or less wisecracking script, the film could easily play as tragedy – but these boys know what they are and what they aren’t, and damned if they won’t face oblivion with smiles on their faces. One of those winning films that’s both an unimpeachable classic and a popcorn-ready Great Time At The Movies.

Our next foray into body horror was Society, a film which realizes “the rich always feed off the poor” in the most twistedly literal fashion. Billy Warlock (hell of a name) stars as Bill Whitney, the teenage son of a wealthy couple who is beginning to suspect he was adopted. When a schoolmate plays him a tape of what appears to be his sister and parents engaging in some kind of wild orgy, Whitney sets to work investigating, and eventually uncovers a conspiracy involving all of high society.

The first three quarters of Society are less horror than thriller, perhaps best described as “Ferris Bueller’s Worst Day Ever.” In spite of the film’s theoretically pointed metaphor, it’s not really interested in meaningfully engaging with class relations; directed by the producer of Re-Animator, it’s mostly content to luxuriate in the vague menace of Bill’s classmates slowly disappearing, and his parents’ consistent refrain of “you’ll make such an important contribution to society.” It finally drops its training weights in the last act, which is brimming with body horror that’s part The Thing, part Akira, and fully gross as hell. I’d have appreciated it if the film did something more intelligent with its metaphor, but can’t deny the power of the incomparable Screaming Mad George’s practical effects – it takes a little while to leave the station, but the final destination is worth it.

We then checked out Ravenous, a horror-western centered on a remote California military outpost called Fort Spencer. Guy Pierce stars as John Boyd, a soldier who loses his nerve and plays dead during the Mexican-American war, but subsequently captures an enemy command post as a result. Due to his combined bravery and cowardice, Boyd is first made captain and then banished to the boonies. Soon, a frostbite-ravaged man named Colqhoun (Robert Carlyle) arrives at Fort Spencer, claiming he is one of the last survivors of an expedition that was forced to turn to cannibalism to survive. Setting out to find the other survivors, Boyd and his companions soon learn that once a man has feasted on his fellows, he becomes something not of this world.

Ravenous is busy as hell, and absolutely uncertain of what it wants to be. The first third or so builds up a relatively convincing western shell, the middle third leans into inconsistently effective horror, and the last third is basically Interview with the Wendigo, with Boyd’s newly cannibal companions attempting to convince him to join their free nation of cannibals. The film’s production involved multiple directors and plenty of behind-the-scenes bickering and recutting, and the final film shows it – tension is raised and deflated basically at random, and characters frequently exit the story without reason or payoff.

Fortunately, strong lead performances and generally excellent cinematography mean it’s at least pleasant to look at, in spite of the preposterously ill-fitting, often chiptunes-adjacent soundtrack. But the film is constantly at war with itself; uncertain if it wants to be scary or poignant, seemingly unhappy with all of its component genres, and too restless to build up a lasting, affecting tone. An unfortunate skip, even before you get to its shamefully boring interpretation of wendigo lore.

Last up for the week was Project A, a Jackie Chan production from his peak Hong Kong era. Flanked by his reliable conspirators Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao, Jackie stars as Sergeant Dragon Ma, a marine policeman intent on tracking down pirates in 19th century Hong Kong. Owing to the intense corruption within his unit, Dragon’s investigations soon find him relieved of his duties – however, with the help of an arms-dealing scoundrel (Hung) and committed police officer (Biao), he eventually finds himself spearheading an operation to take down the pirate lord San Pao.

Project A finds the China Drama Academy brothers at their absolute best: Hung sleazing up the screen while dazzling with his unexpected physical agility, Biao pairing martial mastery with his inherently dignified bearing, and Chan serving as the loveable, laudable hero, while simultaneously putting his body through tortures I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy. Jackie Chan has flung himself onto burning coals, tumbled down a pillar laced with electrified wiring, set himself on fire, and tossed himself off buildings, and Project A’s sixty foot clocktower tumble still stands among the craziest things he has ever done to himself.

That marvelous setpiece aside, Project A is otherwise brimming with stunning clashes of physical acuity and hilarious, death-defying pratfalls. Jackie is a living cartoon character, withstanding more punishment than Elmer Fudd in his pursuit of laughs, and Project A distills the power of his physical comedy down to its wordless essence. Actors like Jackie Chan or Buster Keaton might well be the most natural of film stars, dazzling through their fusion of cinematic trickery, physical agility, and plain simple bravery, embodying the purest spectacle of humans on screen defying the impossible. A wondrous display of kinetic movie magic.