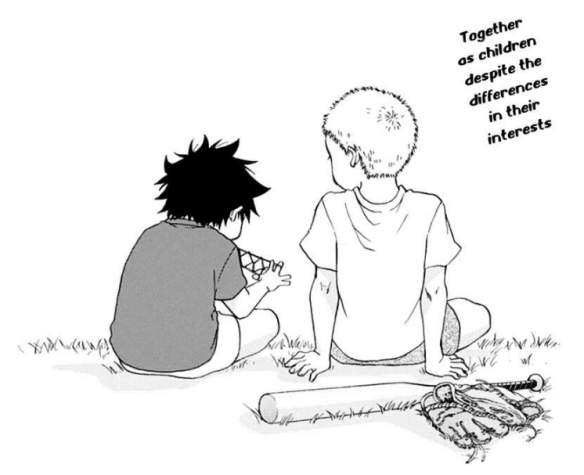

The first image of Blue Flag’s third volume, presented before we even get to its opening chapter, is of Taichi and Touma playing happily as friends, captioned with “Together as children despite the differences in their interests.” It’s a moment that captures a great deal about Blue Flag – the manga’s veneration of the incidental, deeply specific moments that survive in memory and ultimately shape our perception of our own life, as well as its indifference to the superficial markers of alleged kinship or similarity that define so many adolescent relationships. No common interest could equal the bond of shared experience and sympathy connecting Taichi and Touma. The people who are most important to us are not necessarily the people who are most like ourselves – they are those who inform and expand our understanding of both ourselves and others, securing their position among those dazzling incidental fragments that encompass our life in retrospect.

And then, of course, there is KAITO’s meticulous, ever-purposeful paneling. The first page of the volume proper demonstrates KAITO once again in fine form, reveling in the specific specialties of comic storytelling. The reveal of Touma’s broken leg to the rest of his classmates is presented as an overwhelming intrusion on reality – the leg’s sling breaching the panel above, both creating a sense of disruption in the natural order and guiding us towards the focus point of the next panel. And then there is that massive panel itself; extreme foreshortening combines with the natural lines of Touma’s body and the angled gutter above, all intended to draw the eye towards that leg in a cast, making it as inescapable and all-consuming for us as it is for the classmates revealed below.

So much is conveyed without words here, like Taichi’s silent accumulation of guilt as one visitor after another stops in with Touma, each offering their own distinct condolences, each burdening him with their unfulfilled hopes and desires. Taichi’s brow lowers with each unspoken condemnation, watching Touma embody strength and indifference for the sake of everyone else, calmly consoling his teammates and would-be girlfriend even though he’s the one who’s actually hurt. The sequence is a microcosm of the characters’ fears – Touma boldly striding forward into adulthood, embodying maturity as he says goodbye to his childhood dreams, while Taichi and Futaba linger by the door, Taichi too shameful and uncertain to comfort his friend, Futaba too hesitant to comfort Taichi in turn.

It falls to Taichi’s old friend to ask Futaba for support, offering the words that Taichi never could. How could Taichi make this situation about himself, when Touma’s the one who’s suffering, Touma the one who sacrificed his last chance at baseball glory? Of course, we can’t actually control our sense of hurt at times like this, and Taichi has perfectly understandable reasons to feel bad about himself. It’s a frustrating fact of life that many of our ugliest, most uncharitable feelings about ourselves carry with them an inherent implication that we deserve to feel this way, and that any efforts to seek help in overcoming them would only incriminate us further.

Fortunately, that’s not the way Touma sees it. As Taichi apologizes for his alleged crime, Touma fires back “that sort of dream or whatever doesn’t compare to a life. Nothing is more important than you!” His declaration is practically a confession, so direct that Touma himself realizes he’s overstepped both their comfort zones, as depicted through his fiercely narrowed, conviction-filled eyes widening after what he said. But more generally, Touma’s words demonstrate the vast divergence in their perspectives on both each other and the nature of a life’s journey.

Taichi sees himself as a person of little value, because he tends to construct value externally, seeing others as noteworthy because of what they accomplish in athletic or scholastic arenas. Touma sees things very differently – people are “valuable” in his mind because they are a part of his life, a portion of his joy with dreams and passions of their own, regardless of how “exceptional” those passions may be. Touma sees in Taichi his own hope of a happy future; in contrast, Taichi sees nothing in himself, because he can’t appreciate the kindness, concern, and charm that he exudes at all times, the consideration he takes for granted as just “how a person should be.”

Taichi sees a person’s value as defined by external metrics of success, which is why he sees Touma as unreachable, and why he is so desperate to help Futaba not be like himself. But Touma just wants to be around people he loves; that is what is most valuable to him, not childish dreams of becoming a star on the mound. He has been blessed with learning early that life is not a series of medals to be won – it is a collection of moments like the the one that opens this volume, and the great task of life is to ensure your memories are well-furnished with moments such as that.

Having gone too far in declaring Taichi the most important thing in his life, Touma attempts to reassert normalcy by asking “we’re best friends, right?” This pair of panels and the space between them are devastating – Touma anxious yet hopeful, desperate to reclaim his most important relationship, and Taichi mired in regret, hating himself for having somehow preempted Touma’s precious dream. The massive gap between these panels emphasizes the emotional distance between them, the word balloons of Touma’s question standing as a tentative attempt to bridge that gap, a boat sailing from one perception to another. This gulf in perspective is embodied through Taichi’s final words, as he mutters that he is “not worth that much.” Due to his skewed perception of personal value and deeply seeded self-hatred, Taichi cannot see in himself the value that Touma sees.

The arrival of Touma’s brother Seiya offers fresh opportunities for KAITO’s mastery to shine. Here, the angled panels combine with the twisting of Seiya’s neck to evoke a sense of furtive, circuitous motion as Futaba exits the scene, her anxious energy practically spinning Seiya in a circle as he returns to Taichi. In contrast, Seiya’s larger form in each of these panels conveys his strong presence and clear personal confidence, as a man who takes center stage wherever he may be. KAITO is remarkably good at not just conveying individual character dynamics, but also articulating the aura of characters in space, the way certain people seem to either dominate their environment or wilt into the background.

And of course, this extends to the distinctive ways characters see each other, as well. After several pages of Taichi being overwhelmed by memories, lessons, and that overwhelming sense of guilt, the filter of recollection and jumble of disorderly, closely stacked panels gives way to a page of pure white, as he sees Futaba waiting on the subway bench. Through this contrast in paneling, KAITO demonstrates how an unexpected sight can actually clear our minds, can dash our preoccupations and let us live freely in the current moment once again. Every mangaka defines their own visual language, but something like “the silence of a vast white page” is fairly universal, whether it’s applied to the isolating silence of Futaba’s anxiety from the second volume, or the freeing silence of this moment here.

Realizing Taichi needs a break from all the self-hatred, Futaba invites him out to a local park center, only to learn the park is already closed. This disappointment is relayed through another playful flourish of paneling, using the bars as seen through a perspective shot to further emphasize the failure of Futaba’s hopes for their outing. It fits with this manga’s general embracing of the unvarnished reality of interpersonal relations; no one ever gets the “perfect opportunity” to get closer with someone else, we all just do the best we can with the chances we’re afforded. A fact that plays into Blue Flag’s larger themes of embracing life’s opportunities, of becoming more than a bystander in your own life. Our chances to seize the day will always be imperfect, but we must seize them nonetheless.

When Taichi asks why Futaba chose this place, she replies that “it feels like time flows peacefully here.” It’s an offhand remark that seems to embody the brightest hopes of Blue Flag – that these tempestuous storms of identity-finding and shame will pass, and that the characters will eventually find a place where they are happy to wake up as themselves every morning, and to enjoy the time passing without fear of missing out on a better life. We do not need glory or perfection to be happy; all we need is a place where time flows peacefully, where we can happily be ourselves besides people who are happy to be beside us.

Their conversation embodies another key element of Blue Flag’s visual vocabulary: the purposeful interplay of light and shadow. KAITO portrays moments of either emotional relief or fond recollection as almost pure white, as if the memories are shining so brightly you can’t even see the darker details. But as Taichi falls into self-recrimination, a black miasma begins to waft across the panels, steadily consuming his joy and leading him back to anxiety and self-hatred. This contrast embodies an unfortunate truth of memory and self-reflection; our mental impression of events is always filtered through our current perspective, with moments of happiness becoming all the more pure and beautiful in retrospect, while moments of sadness become nothing but sad as well. We are very bad at appreciating the emotional complexity of our past experiences in retrospect, and extremely good at coloring them fully in one shade or another, which makes it all the easier to then unflatteringly compare our current feelings to our past glories.

Taichi’s perspective is relatably self-destructive. He doesn’t want to be pitied or worried about, because he sees himself as the perpetrator of a crime against Touma. As a result, he lashes out against the people attempting to comfort him, because their comforting only makes him feel worse about his actions. And of course, that very act of lashing out also makes him feel worse, since he feels like a bad person for being cruel to the people who care about him. He doesn’t want to be cared about right now – he wants to be alone, suffering for his crimes in a way that for once doesn’t involve the suffering of others. Everyone making an effort to help him is only recreating the original “crime,” in his mind – which again, ultimately comes down to him not seeing himself as worthy of concern.

Locked in this destructive cycle, Taichi tries his best to shove Futaba away, but is fortunately just not very good at being unkind. His best efforts only amount to “it’s impossible for you to like Touma and me equally,” which is obviously a lie, and a fairly toothless challenge at that. Blue Flag refuses to embrace canned misunderstandings or out-of-character explosions in order to justify its drama; human beings are plenty complicated and interesting enough already, if you’re willing to truly pay close attention to what makes us dream, cry, or fall in love with each other. Blue Flag’s nuance of characterization and interaction means its story can feel anthemic without any melodrama; it is embedded in the real substance of imperfect human interactions, and that substance is worthy of sonorous articulation.

Refusing to be pushed away, Futaba is portrayed as the light itself, drawing Taichi out of his self-hatred and even briefly bleaching his hair, so as to better emphasize the glow she casts on the people around her. Dragging him from a sudden rainstorm to a nearby shelter, the two share a perfect moment where no words could suffice, and no words are necessary. Futaba clinging to his hand as they wait out the rain, determined to show she cares about him, no longer caring if she can verbally convince him of how she feels. One hand in another, a moment that sticks in memory, here isolated through the lack of any background art behind those hand-focused panels. In a moment like that, nothing else exists.

Of course, KAITO’s careful presentation can elevate cruelty just as well as comfort. Our return to Touma’s perspective opens with a vicious juxtaposition, as we hear an announcer detailing the ongoing drama of the legendary Koshien high school baseball tournament, with a series of panels shifting from the open sky, to the scene as viewed through a television, to Touma lying helplessly in his hospital bed, his face unreadable but neck muscles clenched. The progression of panels is like a miniature reprise of Touma’s one-time dream drifting out of reach – it should have been him staring up from the stadium at that staggering blue sky, but instead he is imprisoned here, not even capable of walking himself into the stadium seats. Through these panels, the basic technique of progressively zoomed-in establishing shots are transformed into an articulation of a dream destroyed.

Our leads are still suffering a disconnection of intent as Taichi arrives at Touma’s room, revealing that Touma requested that he alone come to watch the baseball game. Taichi believes this is a portion of his punishment – that Touma is demanding he bear witness to what Taichi stole from him, and feel all the more fully the responsibility and regret he should be feeling for destroying Touma’s dream. Obviously, Touma would never think that way; in all likelihood, he wants Taichi here because Taichi is his pillar of strength, and he’s not sure he could bear to watch this game all by himself. We can never know what we mean to each other unless we strive to truly communicate our feelings, and in high school, with the dissolving certainty of childhood meeting the profound anxiety of constructing a mature self, it is all the more difficult to know what others want or mean.

To overcome that disconnect, to rekindle what you once held precious while moving forward towards a newer, happier you, is a difficult and often lonely process. But if you’re brave, if you’re kind, and if you remember what you care about most, it is always possible to reach out. As Taichi stews in his feelings of guilt and regret, desperate to say the right thing yet uncertain what that thing might be, Touma reaches out once more, asking for Taichi to hold his hand through the ninth inning. He admits he is scared, and that Taichi’s presence has always been his comfort in times like this. He acknowledges he needs his best friend now, more than anything else in the world.

Taichi’s mind floods with all the people he thought had every right to judge and to hate him, all the reasons he invented to hate himself. But none of his companions were like that – none of them blamed him, none of them saw in him the disgust he felt towards himself. In fact, they actually tried to comfort him, just like Futaba did. They saw his happiness as worthy and valuable, even after the mistakes he’d made, even despite the distance between them. And in that moment, he is flooded with not shame, but gratitude – a deep, sincere love for all the people in his life, and a desire to repay the faith and kindness they have instilled in him.

In that moment, Taichi grows up in a small but crucial way, seeing himself not as a burden to those around him, but as a bearer of their hopes and generosity who must repay that hope in kind. He begins to see the judgment of others not as a burden or criminal sentence, but as a mutual promise people who care make to each other. He is profoundly grateful for their kindness, and now wishes to become the kind of man who can repay that kindness in turn. While adolescence is frequently defined by anxious worries of being judged or rejected by others, the shift towards a confident, mature self demands rising above such self-inflicted anxieties, realizing you are surrounded by people who care about you, and committing yourself to paying back that love in kind.

We then jump to Futaba’s side of the story, and find her equally mired in the assumptions and expectations of others, some of these actually well-founded. While everyone in high school is generally attempting to figure out their mature self, some people take a much crueler path than others towards that point, and some people frankly just aren’t that nice to others. There is lots of genuine friction in these years, when you’re forced to at least be acquaintances of proximity with many people who you wouldn’t naturally be friends with. It’s a perfect storm for destroying your sense of self-worth, and Futaba’s fears regarding being a burden to the people she cares about are understandable. It’s a good thing she has a friend as frank as Masumi to rely on, someone who cares nothing for the social niceties of high school, and everything for the genuine happiness and success of her friends.

The two share a wonderful breakdown of the complexity of adolescent romantic feelings, as Masumi asks Futaba to describe how exactly she feels about Touma versus Taichi. Hearing Futaba articulate her feelings, it is clear that she cares about both of them, but that her “love” of Touma is more like a distant infatuation, a respect and admiration for what he embodies combined with a clear physical attraction. In contrast, Futaba sees Taichi as a close friend and confidant, someone she can rely on in times of trouble, someone she often forgets is actually a boy. Taichi is practically family to her already, and she could not imagine losing that family. He is the one who makes her feel complete – he is the one she truly loves.

For his own part, in the wake of his revelation during the Koshien game, it is clear that Taichi has grown up a little bit. The last chapter of this volume finds him no longer wallowing in his own insecurities and self-hatred – he realizes that Touma actually has it far worse, and is nonetheless holding it together for the people he cares about. And Taichi sees the strength in that, and wishes to become someone who can ease others’ burdens like Touma, someone who can be relied on in times of trouble. Both Futaba and Touma have been so kind to him, and he now wants to be their pillar of strength in turn. Of course, he’s still Taichi; he doesn’t yet realize how much he already performs that role, even though his friends have told him time and again. Try as we might, it is difficult to express just how much we depend on the people we love.

This article was made possible by reader support. Thank you all for all that you do.